MY MOTHER WAS NOT PLEASED that I chose that day—the day of the Oklahoma City bombings—to leave my father’s side. Forever.

There was nothing I could do. Had I been a surgeon or a shaman, I would have stayed to open his body or his soul to cure. But I was neither and comfort was the only thing left to offer and that offering would best come to my dying father in the form of morphine.

There was nothing left unsaid by me to Dad, although later, when it was too late, I would wonder about that. I say that only because we never really talked much, so there must have been a lot that was left unsaid. But I don’t know what those words would be.

And I had a family to get back to, something I know he would have understood could he have understood anything at that point.

He would die knowing that I loved him, me knowing that he loved me. In the end, I guess that’s all there really was. It would have to be enough.

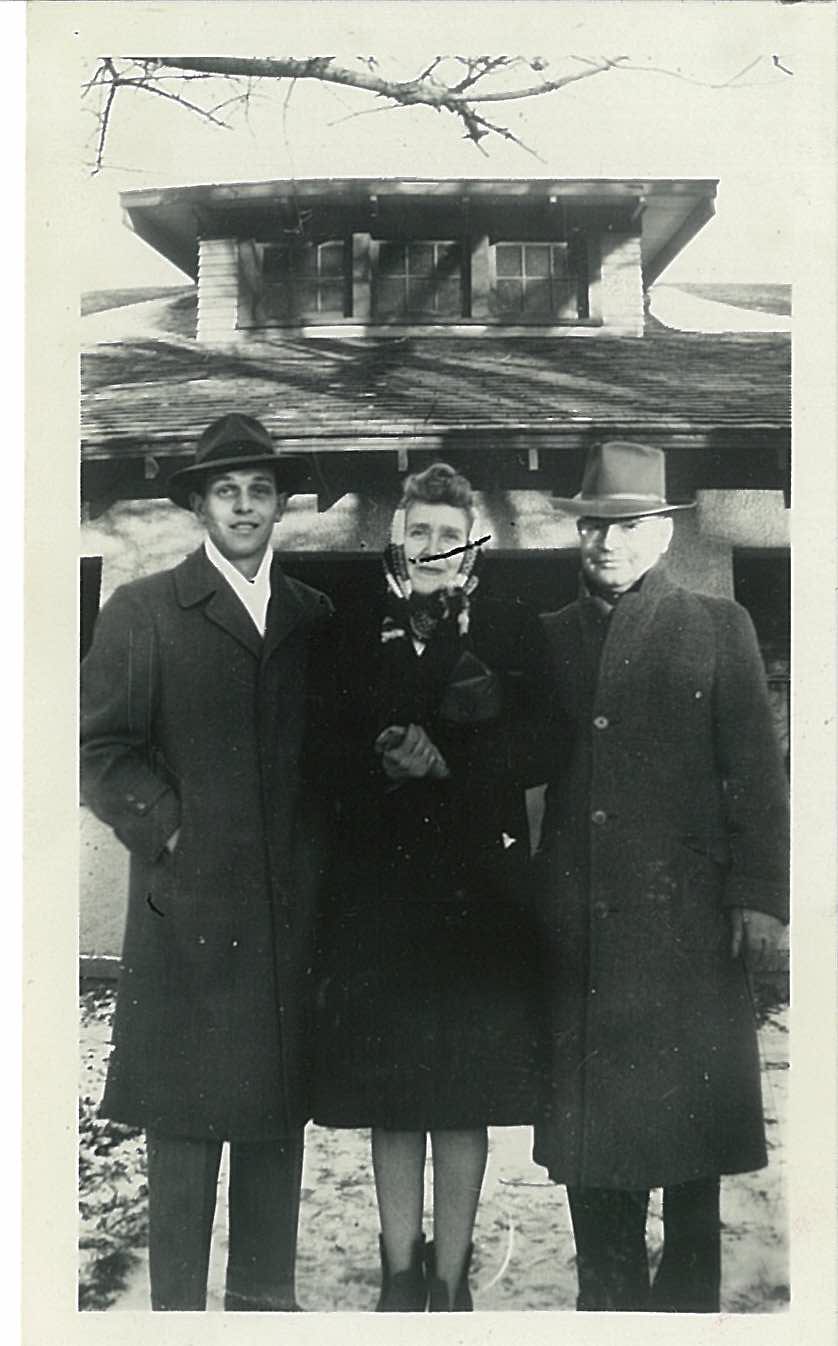

He had been the best man at my wedding.

I HEADED DIRECTLY TO THE CITY, thirty-five miles east, found his parent’s graves at the Bohemian National Cemetery on Chicago’s near North side and paid my respects. The sculpted cement monument was a weathered gray tree trunk ornamented with acorns and squirrels. I don’t know why; I don’t know the significance of those adornments. There’s a space for me there should I so choose (I don’t); it was gifted to my parents on the occasion of my birth. Bohemians are a cheerful lot.

“We mourn a birth and celebrate a death,” Dad told me on more than one occasion.

Pointing my truck west, I left Interstate 88 for Route 30 and traversed the two-lane back roads of Illinois and Iowa, avoiding the highways and slowing down every eight, ten or twelve miles or so—distances determined a long time ago by how far a horse traveled in a day, I’ve been told, along game paths that had once led to salt sources—as I approached the little towns along the way, each one quaintly similar to the one before. Every town had an official posting of its name, population and altitude, the latter of which varied little across the vast plains; nearby were postings of the service clubs, fraternal orders and churches active in the area. There is a comforting sameness, this route through the neglected burgs of Middle America, this path rendered obsolete by modernity, convenience and speed.

I wish I’d have been traveling through these towns on a Sunday, if only to hear the ringing of church bells, melodic reminders to congregants to gather as friends and neighbors, offer thanks for their blessings, and take quiet solace for an hour or so.

I prefer the back roads because one doesn’t see many towns from the Interstate. One can’t. Those insidious billboards offering the tired messages of the cluster of fast-food restaurants and chain hotels, each exit garishly similar with their towering fluorescent signs to the ones last passed and each defying, or denying, travelers to find something of interest beyond the proscribed borders of the cloverleaf access.

One must leave the highway to slow down.

One must leave the highway to discover what is left of an older America.

I eventually got to my first destination: Broken Bow, Nebraska, a city almost dead-center in the state. I checked into a modest roadside motel on the edge of town that had a restaurant offering a decent chicken-fried steak—a dish I find somehow appropriate and comforting whenever I’m in Nebraska—and a bar at the front of the parking lot. I wandered around the town on a blustery April afternoon.

The museum that housed some of my family’s history was closed, but the office of the Custer County Chief was open and I spent a few hours turning the fragile pages of some first drafts of local history.

IT WAS IN BROKEN BOW, NEBRASKA, that my mother’s paternal grandfather, an attorney of some renown (“one of the best known lawyers and odd characters in Western Nebraska,” a newspaper obituary said in its November 24, 1899, edition), had been shot to death on the courthouse steps during a trial in which he was boldly defending a murderer. It was the victim’s brother who murdered my great-grandfather there on the edge of the town square.

James Corbin Naylor, a native of West Virginia, fancied himself a poet, who in retrospect no doubt admired his Indian-hunting father-in-law, a Welshman named Frank Morgan. J.C., or Judge, as my great-grandfather had been called, had studied the law while guiding freight wagons from the Missouri River to Denver. After having spent some time in Iowa jails for his resistance to abolitionists, he had settled in Callaway, Nebraska, where he had been a “picturesque character.” His sins apparently forgiven, or perhaps never revealed to his constituents, he became a judge.

Apparently, he also had a law practice, which may or may not have been common for judges in those days. It doesn’t matter anymore. He was known as a “sarcastic writer and a good pleader in criminal cases, and had it not been for his personal habits and unfortunate appetite for strong drink he might have acquired competence and honors.”

What all of that boils down to is that J.C. Naylor, my great-grandfather, was a drunk, and he died of alcohol poisoning in his bed at the Morrissey Hotel and Restaurant in Broken Bow in 1899. The murder weapon was whiskey and none of his blood was ever spilled on the courthouse steps, though his vomit undoubtedly dirtied the bedclothes and floor beside his bed.

For more than forty years I had been passing along the family lie of a man the local newspaper called an “odd landmark of the community” who left his family “in destitute circumstances.” The members of the Nebraska Bar Association paid his funeral expenses.

My mother’s father, who was five-years-old when his father died, was so desperate to maintain respectability that he lied about the very events that are not all that uncommon in other families. He had fabricated a story that turned his father into a hero and kept it alive until well past his own death.

I visited the Judge’s grave in nearby Callaway that April day, along with those of his second wife and my maternal grandparents, as well as my mother’s maternal grandparents who were, in fact, quiet, kind and humble people who farmed a small plot of land they had homesteaded and about whom no wonderfully romantic stories ever had been concocted, though my great-grandfather, Immer, had served on the school board.

“They had chickens,” my mother told me, pretty much capturing the essence of their simple lives. “They lived in a sod house.”

MONTANA SEEMED WELCOMING AS I CROSSED over the border from Wyoming, traversing a route through the Crow reservation and Billings before heading west. I stopped at a grave site on the frontage road along I-90 near Reed Point to learn about a widower, William Thomas, his eight-year-old son Charley, and a Canadian teamster named Joseph Schultz who had traveled from Prairie Ridge, Illinois, to Montana to seek a new life. They had been killed by Lakota warriors there near the confluence of the Yellowstone River and Bridger Creek on a hot August day in 1866. Jim Welch, the Blackfeet writer whose Killing Custer is the best book I’ve ever read about that particular chapter in our sadly, mostly successful genocidal effort against native Americans, had told me about this tiny roadside memorial. It is quietly profound, understated, and I have returned there often.

It is a good place to contemplate death and imagine the pasts of others. The sounds of the I-90 traffic are muffled by the wind blowing through the tall grasses.

DAD WAS SCHEDULED TO DIE on Wednesday, May 3, 1995.

“Art has, three, maybe five days,” the doctor told my mother. She split the difference and called me with the date.

Geri and I went to the schools to make the arrangements to take the kids out of school for the trip back east for remembrances and interment.

“I’m so sorry,” said the school principal. “When did he pass?”

“This coming Wednesday. It’s on the schedule.”

We headed an industrial-looking white rental van with Idaho plates east and were just outside of Madison, Wisconsin, when we got the news on Geri’s mobile telephone, a leaden contraption encased in an attaché that had been her fortieth birthday present a few months earlier.

It was Wednesday and he had dutifully adhered to the schedule my mother had devised. He was dead. The services had been arranged, a reception hall rented, the caterer hired. Everything had fallen into place, right on schedule. Let the mourning begin.

I wept quietly behind the wheel of the rental van as I steered our way through Beloit and Rockford and on to St. Charles. The kids loved their Grandpa, and Geri thought the world of him, too. We drove silently to the condo apartment (I’ve lost count of which home that one was) where I knew that any opportunity for contemplative silence would be replaced by on-demand hysteria.

WHEN MY MOTHER’S FATHER DIED, thirty-three years before, we made the drive to Nebraska, my mother sobbing in time to the relentless thumping of the tires against the concrete breaks of U.S. Route 6 for the better part of two days. Finally in Imperial, near the Colorado border, my mother’s mourning and her mother’s mourning grew into a bizarre competition of whose loss was greater. “He was my daddy,” she cried. “He was my husband,” she cried. Although my father, at one time an officer and always a gentleman, would never have uttered such a phrase in polite company, I’m sure was thinking, “He was an asshole.”

James Corbin Naylor, Jr., was a teetotaler newspaper publisher, the progenitor of rather elaborate lies about his father, and a New Deal Democrat who loved mankind and had absolutely no use for people. He believed that the great majority of Americans didn’t have the sense to come in out of the rain and therefore should be taken care of by those who did have the sense to come in out of the rain, namely, those elected officials who had gained office after garnering votes from the aforementioned senseless.

Politics can be tricky and are always cumbersome.

Granddad Naylor had no sense of humor, a personality trait he passed on to my mother, and my mother in turn passed on to my sister. He did not suffer fools at all, let alone gladly—peculiar for a man in the newspaper business. He took nothing in stride. He worried about everything, another trait my mother inherited, and possibly gave to me, although I prefer to think that mine is more from the Bohemian side of my genetic pool.

The difference between the two, of course, is that I don’t worry that things might turn out badly; I just accept the fact that they will.

From what I could tell and now remember, was that Granddad didn’t much care for children, although he tolerated my sister and me as long as we didn’t let the screen door slam or talk about things that didn’t interest him which, as little as we were, pretty much demanded our total silence. Nobody could breathe a word or enter the room while he was watching the weekly broadcast of “Perry Mason” on his black-and-white console television set.

He loved dogs because, I believe, dogs are generally obedient and don’t complain much, qualities he admired in mammals. As long as you give them a little something, they’re happy.

He pretty much viewed people that way, too.

It seems to me that his only redeeming quality, other than being a decent writer, a Democrat and liking dogs, was that he loved baseball.

Granddad’s funeral at the First Methodist Church (do they name those places anticipating that a second one will open?) in Imperial, Nebraska, was well attended. He was widely admired, respected and feared (remember, he owned the town’s only newspaper). He was also profoundly disliked. He was thirty-second degree Mason and a laic minister who spent many a Sunday evening preaching in little towns of western Nebraska. As payment for his diligent work on behalf of the Democratic Party in a notoriously Republican state (none of which, in the long run, had really paid off) his funeral was attended by two chartered planeloads of officious, dark-suited Democrats from Lincoln, Nebraska, and Washington, D.C., who sat flanking the minister on the church’s altar, sweating uncomfortably in the sweltering heat of a July day in Nebraska.

Oh, did I mention that his funeral was on my mother’s birthday? Believe me that did not help, though it might have given her a little leverage over her mother’s sense of sorrow, whose birthday was in June.

Many of the dignitaries were noticeably checking their watches as if they either might have another appointment or wish they had. None of them wanted to hang around to sing “Happy Birthday” to my mother—an event that didn’t happen, but if it had, she would have found to have been a loving and respectful act that the rest of us would have found just macabre.

The day after his funeral service, my grandmother, who my sister and I called MeMa, drove me the block or two to Einspar’s Drug Store in the ’62 Chevy Bel Air I would buy from her seven years later for a chocolate soda. She told me that while she loved her husband she was now ready to lead her own life. It would be years before I figured out what she had meant.

The next day we followed the hearse to Callaway and watched Granddad’s casket be lowered into the ground. I liked the finality of that, but being claustrophobic it’s the last thing I would wish for myself. We spent the afternoon with people my family barely remembered and I certainly didn’t know, ate a pot luck supper of casseroles, macaroni salads, Jell-O concoctions with shredded carrots and/or marshmallows and unadorned sheet cakes (what exactly should one script on a cake at a funeral reception?), and returned to Imperial.

The next night, we went to the picture show and saw Auntie Mame, a movie released four years earlier that my grandfather would have truly loathed.

MY MOTHER, WHO HAD ALWAYS LED her own life (Dad was always there to handle the details, however), could turn on the tears with faucet-like precision. Just as she had at her father’s funeral, hot- and cold-running emotions flooded the St. Charles apartment to choruses of “me-me, poor-poor-pitiful me” while my sister, with her own peculiar expression of grief, recalled how much more like Dad she was than I, from facial bone structure to complexion to temperament.

Really, Jo? Whatever.

I was given the task of retrieving my father’s ashes from a local mortuary and when I returned with the cardboard box containing an urn of his remains another predictable flood of tears poured forth.

“This is all that’s left of your father,” Mom wailed, hoisting the box over her head as if it were a trophy.

I believed differently, choosing, rather, to focus on memories—even if there weren’t a lot of them—but arguing with my mother at this stage in her bereavement seemed pointless.

Actually, arguing with my mother had always seemed pointless.

MY DAD WAS TOUGH AS NAILS and yet he was the kindest man I have ever known. Our biggest disagreement in forty-four years came over my opposition to the Vietnam War; his biggest disappointment was when I was arrested for flag desecration. He came around to believing that his war was the last good war, and that it was fought, in a very small part, so that I could desecrate a flag. He cried when the two of us went to a multiplex cinema in suburban Los Angeles to watch The Killing Fields. The last movie we had seen together in a theater was The Odd Couple, and the one before that was Auntie Mame.

In some ways, I think he may have wanted to talk with me more, but maybe couldn’t figure out how. For that, I will forever be sorry. We got mildly drunk on scotch together in a car on a country lane outside of Imperial, Nebraska, once (MeMa did not allow alcohol in her house) and he told me that he would never fear dying because after his experiences in World War II—from the D-Day invasion to his third wounding in Holland—every single day was a gift, every day just icing on a cake that so many others never got to taste.

My mother, who was not with us in that car, insisted that he never uttered such words. To her, his death was less an end of his life than it was an inconvenient abandonment of her.

In retrospect, I know that I should have taken a different tone with Dad from time to time. Although uneducated and unread, he was every bit as smart as I imagined myself to be. I’ve had time to think about this and have to come to believe that he was probably smarter because he didn’t feel any urgent need to defend his positions or convince me or anyone else to share his beliefs.

At times, he breathed easily while I gasped.

THAT HIS SERVICE WAS HELD IN GENEVA, a one-time bastion of racial bias, was ironic perhaps, but it was well attended, mostly by a diverse array of former employees to whom he had offered opportunity. He employed many older people, but he mostly employed high school kids, many of whom were minorities, and he thought that those young applicants who claimed to aspire to a career in his employ were “full of it.” He opted to hire those kids who merely wanted to earn the money they needed to go to college or to augment their wardrobes or to buy a car and were honest enough to say so.

Many of them came that day to pay their respects, to tell their stories of gratitude and admiration.

His ashes were interred on a rainy spring day at Arlington National Cemetery after a ceremony that was both respectful and impressive with its brass band, rider-less horse, black-draped caisson, 21-gun salute and final taps—a distant bugle, its soft tones echoing through the trees, headstones and monuments—and, finally, a military honor guard thanking my mother, on behalf of the President and a grateful nation, for her husband’s service to our country as he handed her the crisply folded flag.

“Art would have loved it,” my brother-in-law noted at lunch after the interment.

My mother, whose own remains were to be interred with her husband’s, wondered aloud if she might be afforded the same ceremony.