My sister died a little more than a year ago and I have finally achieved a certain sense of closure because those various end-of-life folks who helped her transition, or cross to the other side, or whatever euphemism might seem appropriately in vogue, have finally stopped inviting me to her memorial services, of which there have been at least four.

I’ve not gone to any of them.

Jo, my sister, did not want any services. Apparently the end-of-life folks didn’t get the memo.

She had been a devoutly practicing atheist for the first sixty-six years of her life and from what I can tell she made a sudden, unexplained conversion to Catholicism shortly after being diagnosed with the cancer that would be her undoing two years later. Religious conversions like hers happen with great frequency and it really isn’t unexplained. “Desperate” is perhaps the more appropriate word.

Many atheists, when confronted with the realization that death is more than an abstract concept, sigh a heavily intoned “uh-oh” and wonder if it might be too late to, well, you know, sort of wave sheepishly to the heavens and tell God that they were only kidding.

Believing in a greater being and discovering you were wrong is a much better gamble than not believing in a greater being and then learning that you were wrong. By then it’s too damn late to do anything about it. Many believe there may be a Welcome Mat on the top step leading down to a world of eternal hurt.

The tout’s best advice is to hedge your bets. Or at least try to behave, which is pretty much the same thing.

While her late-in-life conversion might have been seen as a last-ditch effort at salvation, it might have had something to do with her getting a DUI. A priest, whom we’ll call Father John as she did, helped mitigate a settlement with the Court charged with administering her trial and punishment. She’d never told me about that little chapter from her life. Friends of hers told me as she was slipping into the cosmic ether. Later, I read Father John’s letter to the Court.

Jo willed her body to science. Actually, it was less to “science” than it was to a mid-western university medical school. (It doesn’t matter which one.) She had confided to me once that her decision to will her remains was because she believed that only deep scientific inquiry could ever discover the mysterious workings of her remarkable mind. She was serious. I tried not to laugh, but failed.

Not to denigrate her considerable academic achievements in non-verbal communication theory, my sister did not have a sense of humor. She did, however, have a penchant for certain verbal affectations (she lived in a house, but would have preferred a “flat,” and her auto ran on “petrol”). Her insistent mispronunciation our own home town, “chah-KAH-gah,” drove me nuts. She had a bizarre obsession with Victorian tea service.

Her generosity of self has to be admired, along with her odd sense of altruism, however. Medical schools need cadavers to do things that the administrator of the school told me would be “forensic in nature.” Brain cells may or may not be involved.

When I hear the word “forensic,” I think exactly what Webster has to say about it: “the application of scientific knowledge to legal problems; esp : scientific analysis of physical evidence (as from a crime scene).”

I interviewed Jerry Vale once. Not the ’50s Vegas lounge singer, mind you, but the forensic odontologist with the L.A. County Coroner’s Department. Dr. Vale was the guy who identified and sourced the manufacturers of the pliers that had been used to torture the two-year-old Amy Sue Sietz by Theodore Frank before he killed her in 1978.

That was my introduction to forensics, as well as to the quite dreary L.A. County morgue, and I wondered how “forensic in nature” might apply to my sister whose only crime, other than mispronouncing Chicago, was one count of drunk driving. I thought that any forensic studies in her case might be a bit extreme. Especially this long after the fact.

Donating one’s body to science, as it were, is a win-win kind of thing. Survivors don’t have to pay for the disposal of the remains. No casket, no hearse, no cremation, no guest book, no generic organ music. The donee picks up the donor and takes said donor to a lab or somewhere they deem appropriate and that’s about it.

But there is more to it than that. There is always more to it than that. Always.

The morning after my sister died I talked to the guy who introduced the whole “forensic-in-nature” concept to me. He was a couple of hundred miles away and I got the impression that my sister’s remains might be as close to him as in the next room. I mentioned the “remarkable” mind thing and I could tell he wanted to laugh. He was very professional though and so he didn’t. I laughed enough for both of us.

Life goes on, and several weeks later I got a letter from the Director of the Dead at the cold-storage part of the medical college that my sister now called home. He wanted pictures of my sister and stories about her life. The letter expressed a sincere desire to share with his fellow medical-students-working-with-dead-people information that would allow them to get to know my sister on a deeper, perhaps even spiritual level.

As her only living relative, he thought I would be the right person to supply them with such artifacts.

I thought he was the right person to secure lodging in a rubber room.

For all of the obvious reasons, I ignored his request. But he was persistent and I received another communique from him. The message was the same, but this one was sent FedEx and was augmented with the curriculum vitae of about 35 medical students who offered their own reasons for wanting illustrated and anecdotal information about my dead sister. None of them mentioned the search for the secrets of a “remarkable mind” which, if they had, might have piqued my curiosity.

As it was, I found it to be borderline creepy. I could not rid my mind’s eye of a vision of my sheet-covered sister prostrate on a stainless steel gurney as students in white lab coats―scalpels and retractors in hand―joyously danced around her like ghostly gnomes singing a spritely rendition of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Getting to Know You.”

A third request addressed to me arrived and I scrawled “Deceased” across the envelope. I’ve not heard from them since.

Hospice, however, is another story.

Of all the fields of caring for people that there are, there is not one for which I have more respect and admiration than Hospice. The people who work in that field are angels awaiting their wings. Their every working day is spent caring for people who are on their way out while trying to help and console the family members and friends who each have a uniquely different approach to the inevitable.

Jo died of complications of esophageal cancer. A horrific surgery preceded her death by two years. I was with her following that operation for a month or so, and I was disheartened by her disregard of her doctors’ orders. She might have lived another couple of years had she made better choices, but we all make bad decisions.

The fork in the road provides not two, but three options.

Things had worsened and she was scheduled for another surgery that I didn’t think I could get to because I was recuperating from a surgery of my own. Her doctor called to tell me that the cancer had metastasized widely and that surgery was no longer an option.

“We’ll do whatever we can to keep her comfortable.” As reassuring as those words are meant to be, one hates to hear them.

I got to her hospital bedside the next evening and held her frail hand, listening to her life’s pulses being measured in glowing beeps. In the morning we arranged her transfer to Hospice―a lodge-like setting in a gentle swale of beautiful woods with willows bending to the late-winter breeze. It seemed like a most acceptable place for my sister to die. I sat at her bedside and watched the quite predictable progression of death envelop her. It took less than thirty-six hours, during which time I met many of her friends and tried my best to fill in the blanks they didn’t know about her life before they had come to know her.

Then I drove her bright-yellow car to her home across town. Her dogs greeted me with wagging tails. I was exhausted. My sister was dead.

The next afternoon I went back to say thank you and goodbye to the good people of Hospice. There was a lot of hugging and the staff loaded me down with pamphlets and brochures offering well-considered and thoughtful guidance through that bereavement process I would be obliged to own in the coming days and weeks or months. There were more hugs and promises to keep in touch, exchanges of e-mail addresses and offers of help. There were some final hugs.

I never really looked at the materials they gave me. It’s not my way. I’ve never allowed myself to appear very serious or vulnerable in those moments. Denial? Survival? Somebody else can make that call. A quick one-liner has always been my coping mechanism, my own best defense against even the remotest possibility of emotional assault.

I’m a secular humorist. Ba-rum-pum―Tsssh!

Every couple of months or so I would receive an invitation from my sister’s Hospice folks to participate in a group memorial service for her and others who had passed through their caring hands. I never went, or even responded. The invitations have stopped. Closure.

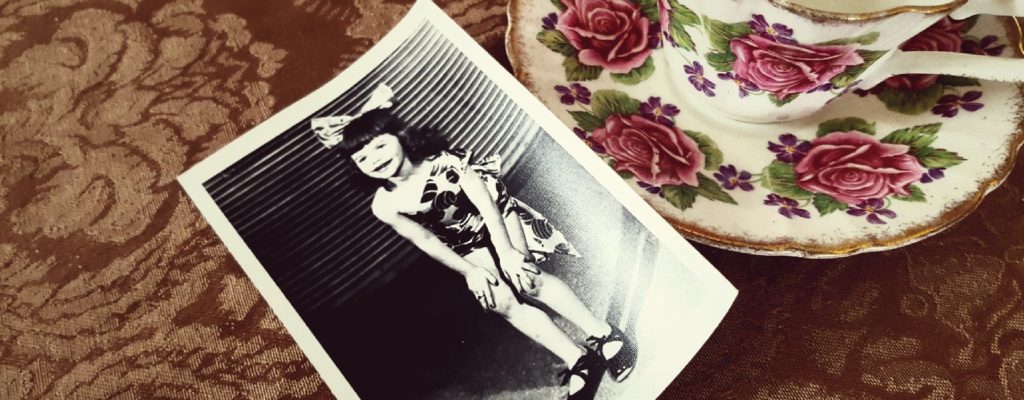

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

Beautiful, jimmy. How real.

Yeah, Pascal’s Wager. I noticed as kid the evil gunslingers always seemed to find God as they lay dying in front of the sheriff. For many, the caring ceremonies you describe are comforting, and often, hospice and others have a knowledge of our loved ones we cannot fathom. Each one of us has distinct and different notion of who our loved ones are, limited or strengthened by what they have revealed to us, or not. Death is the big quandary. I guess we’ll all find out in the end.

Provocative as usual Jim, and timely for me because I had just posted this possibility for botanical reincarnation. Personally I’d opt for an aspen seed to insure the spread of my post-death self through cloning.

Vis-à-vis donation to science, when I reach the do not use beyond date, I have chosen to have my body donated to the med school at Montana State. Perhaps I am overcome with vanity to think that there might be anything of value in my age-ravaged remains, but who knows. Anyway, it will save my kids from the unconscionably high cost of conventional interment. It will spare them of having to deal with an obsequious funeral director, like the one played to perfection by Liberace in the brilliant 1965 film adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One. No Mr. Joyboy will inject me with formalin.

https://www.facebook.com/Fernfeeler/posts/10214831963967711

Thanks for your support and input, George. Be sure to have some photos and anecdotes selected to accompany the remains! (HaHa)

?

Hi Jim.

Great writing as always but whew, this one hit home. Your reaction to the tragedies of life is similar to my own. Developed my “morgue” humor working in the morgue in Vietnam. When you’re “processing” 100 a week you’d better develop one. Anyway I’ve outlived my Dad and Mom, my sister and nephew, two ex wives and am not in contact with any other blood relations except for my son and his children. I’ve met those losses with a shrug and a hug to comfort those around me. It isn’t that I didn’t love them. It isn’t that I don’t care. But no one gets out alive and life is for the living. Thanks for the article.

Thanks, as always, for your input. Everybody handles death in their own way and there is no right or wrong way. Hope your birthday was a nice one. Stay healthy.

Hi Jim. For some unknown reason, your name popped into my head. I googled you and found this amazing blog. The picture you painted of Jo was spot on. Had I written something about your sister the words “flat, petrol and (I would add ) ring up and lift” would be included. ? I hope you are doing well! I look forward to reading all of these!

Thanks for finding me! I appreciate your interest and wish that Jo would have seen some of my work. Hope you are well and safe in these troubling times.