If a musician’s direction to Carnegie Hall is “Practice, practice, practice,” the same could be applied to any number of vocations. After all, practice can lead one to the very edge of perfection.

I have very mixed thoughts about the source of certain abilities in the loosely defined world of the arts. If God is invoked—as in “it’s a gift” or “it’s a God-given talent”—the door closes on further discussion. Such conclusions would, by strict definition, eliminate the need for “practice,” the talent and demonstration of same being an innate property of the individual that emerges like a butterfly from its cocoon. An argument more acceptable on its face might be made that the “gifted” part of the equation represents only a percentage of achievement, the rest being attributed to study and practice.

Along those same lines, it’s doubtful that Michael Jordan or Joe DiMaggio, to name but two, achieved their athletic success and fame because some deity deemed it so. I suspect that both legends spent countless hours on the court and on the diamond working toward their quests.

There might be some merit to a certain genetic disposition, but I believe such hand-me-down abilities are more likely to be environmental. My maternal grandfather was a newspaper writer and editor and when I came to pursue a similar vocation, it was widely assumed that I had “ink in my blood.” (I can assure you, I don’t.)

And yet, considering any environment in which a child might be raised, I can think of few examples of a child achieving the success of one of his or her parents in any of the creative arts. While some of that might be attributed to a simple fear of not being able to match the parent’s achievement, or the chance of being compared, it is just as likely that Rembrandt’s kid just couldn’t master the application of egg tempera to canvas—if he ever tried.

Of the twenty children J.S. Bach sired, only C.P.E. assumed the composer’s mantle of his father’s.

Aptitude is certainly worthy of consideration. Perhaps the hard-wiring of the brain, certainly a luck-of-the-draw proposition at best, provides a basis to steer some to science and others to the arts and letters. I happen to think it is exposure and interest that drives pursuit. But can the skills needed in the arts and letters be taught?

My friend Richard Wheeler, whose eighty-plus published books might rival the number of books many have even read, addressed the issue:

I stumbled into the world of literary art accidentally. Stories were a way to make a buck and allow me to escape hamburger-flipping. I used to call artists artsy-fartsy, which betrays my prejudices. I think MFAs in creative writing are a stretch. Writing itself barely rises to the artisan level, and one needs no more than the “Chicago Manual of Style” to do a workmanlike job. Those with something to say don’t study writing or pursue art; they get out in the world and live hard and tell us about it. My views softened a little when I met artists I admire.

Writers don’t agree on the issue of whether writing can be taught. There is no shortage of MFA programs and writer’s workshops, seminars and retreats scattered across the country that attract thousands of would-be writers. How many writers they produce is another question.

I took a graduate seminar course in writing at the University of Illinois. Each week the students (there were maybe ten of us) would write a 750-word essay—typed, triple-spaced—that we would read aloud in class. Comments and criticisms were then offered. Many were dismissive and cruel. One’s moment in this expository sun felt like being the honoree at a Friar’s Club roast with insults that weren’t meant to be funny. Then the professor would collect the essays and type his own corrections, suggestions, criticisms, etc., and return them to us at the next session. All of this—a bleak fraternity of other fledgling writers, the unquestioned authority of the instructor—could easily have led to self-doubt, suspicion and a touch of paranoia.

AS A YOUNG DRUM STUDENT I used to play Buddy Rich’s recorded solos at 16 rpm and transcribe—note-by-note—his solos. I would then practice them—note-by-note—until I had them down pat at full tempo. I did the same with records featuring Elvin Jones, Max Roach and Art Blakey. I could have sat in for Gene Krupa on “Sing, Sing, “Sing.”

My imitation of these great jazz masters wasn’t meant as flattery. It was meant for me to learn as much as I could about the craft of drumming. It was meant to help develop my own interpretative approach (style) on the drum kit. Once the rudiments were mastered, it was time to break the rules.

As a senior at Interlochen Arts Academy, an instructor of English took an interest in my assigned essays and started encouraging me to pursue writing.

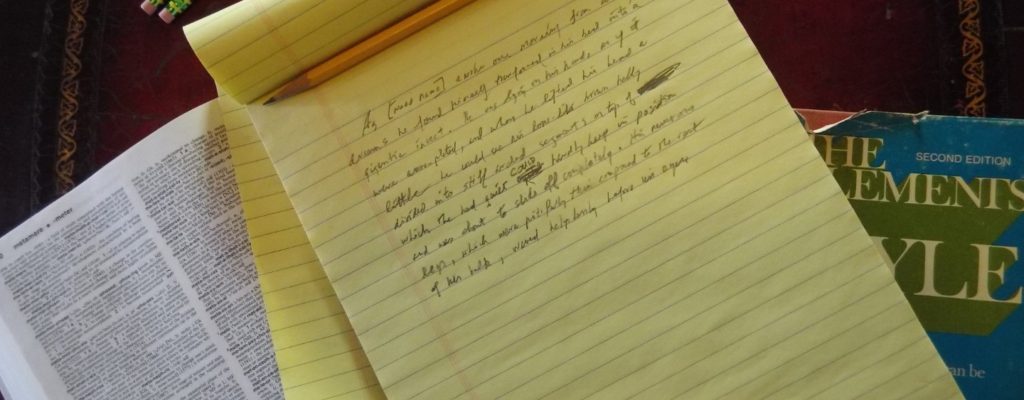

How does one become a writer? She had no easy answer, no text to reference, no list of do’s and don’ts, no set of rules and regulations. She supposed that exposure to literature couldn’t hurt and encouraged me to read, absorbing the styles and structures in books that I found appealing. She also gave me a hardback copy of Strunk and White’s “The Elements of Style.” (I still have it and keep it near at hand.)

At the time, I was reading D.H. Lawrence, Thomas Hardy, Herman Hesse and John Cheever, whose style and structure seemed almost unnoticeable in his masterful story telling. Cheever’s short stories hit home in a home I longed for. His patrician grace, the suburban alcoholism and misbehavior, the absurdity of it all. There was within a contemptibly admirable attitude.

Though not wanting to be John Cheever (although I admired his New England haughtiness) I did want to learn his solos at 16 rpm. I made it my job to type his stories—ten or twelve of them, I suppose—and pay close attention to every detail in his writing.

I don’t write short stories, but I took what I learned from typing Cheever and reading as much as I could to my chosen field of journalism, where writing frequently takes a back seat to reporting (as it may well should).

More than anything, writing, along with any of its creative cousins in the wide world of the arts, is a craft that is honed with practice and discipline. The necessary rudiments can be taught, but the rule-breaking comes later. That’s up to you. In the meantime, “Practice, practice, practice.”

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

Jim you have written a wise and thought provoking article. Human beings are never simple; I agree that there are many, factors that influence a person’s gifts/achievement. Practice is certainly one of them but heredity, environment, and personality all play a role. Anyway,I thought your article well thought and articulate. I see that I need to read your blog more often!

Thanks so much for your comments. They are truly appreciated.

Excellent explanation as to how practice, not just aptitude makes for a great craftsman, artist, musician, and so forth. PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE!!!!

Thank you.