The only thing predictable about the weather in Montana is that it has a tendency to change every ten minutes or so–for better or for worse.

When we moved here almost twenty-five years ago I was looking forward to four distinct seasons–something I missed during the seventeen years I spent in Los Angeles where the weather tended to vacillate wildly between hot and hotter. I had grown up in Chicago enjoying and/or enduring the seasons: the orderly progression from spring to summer to fall to winter and its attendant climactic changes expressed in light, color, humidity, wind speed and temperature. What took me by surprise in Montana was that those four seasons frequently occur over the course of just a few days.

I have seen it snow in every calendar month. I have also seen temperatures in the 60s in every calendar month as well. And the wind? Well, it is a constant that runs the gamut from “what a nice cooling breeze” to “did your house blow over last night?”

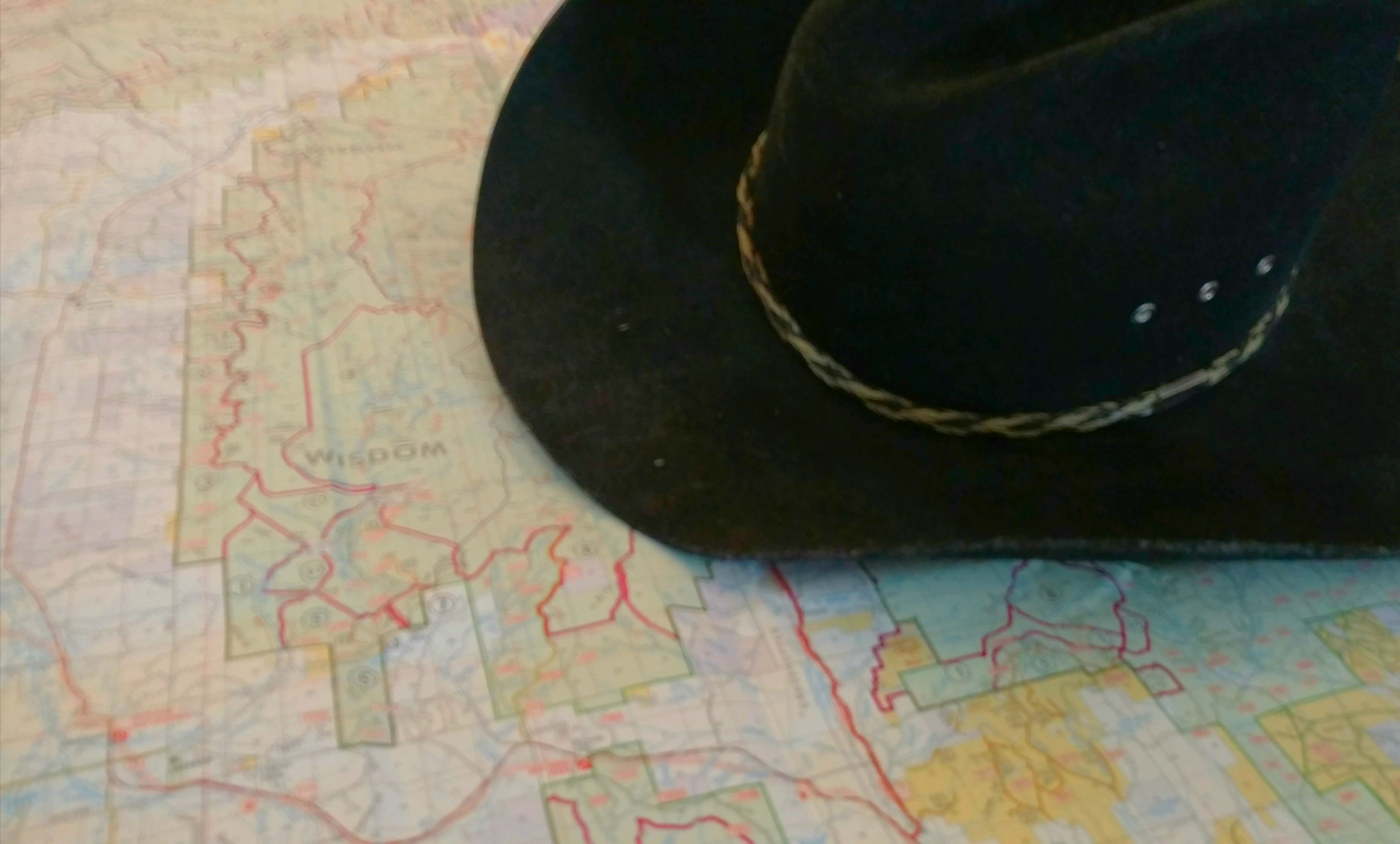

So without consulting either a calendar or a Smart phone, the only way we really know that it’s summer in Montana is by the proliferation of cowboy hats being worn by people in Bermuda shorts and sandals (with or without socks). We affectionately call these folks “tourists,” and they start appearing about now–Memorial Day weekend, which is the official start of the summer season and the very moment in time that gas prices reach a high that won’t abate until the official end of summer on Labor Day.

I’ve observed a lot of changes over the years here in the Last Best Place. We don’t seem to get those long stretches of sub-zero temperatures we used to endure–those couple of mid-winter weeks during which an old rancher told me the best thing to do was to sit close to the wood stove and read a good book. We also don’t see a lot of cowboy hats. Unless they’re going to church, out on the town, or to the bank, the modern rancher is more likely to be seen wearing a baseball cap than a Stetson.

And while I can’t recall ever seeing (or even imagining) any of the ranchers I know wearing Bermuda shorts or sandals, neither of which offer much protection from rattlesnakes, I’d be willing to bet that not one of them would choose to complete the outfit with a wide-brimmed felt hat.

The cowboy hat trade is suffering, its mainstay customers coming from the ranks of country music performers and tourists visiting places that promise glimpses of the Wild West.

I was barely past my teens when I lived in New York City and I must have had a look about me that said, “Ask. I can help.” Complete strangers would stop me on the sidewalks to ask for directions. You could tell they were tourists not just by their odd manner of dress (what is that about tourists, anyway?), the cameras slung from their necks or the mis-folded maps they clutched that were, apparently, useless. No, you could tell they were tourists because they stopped strangers on the streets of Manhattan. In those days, before Rudolph Giuliani turned Times Square into Disneyland, confined drug addicts to Rikers Island, and sent the criminal element packing off to the outer boroughs and New Jersey, New Yorkers did not do that sort of thing.

Not only did we not talk to strangers, we didn’t even risk making eye contact with them.

I am to this day perplexed by the process, or lack thereof, that people use to choose who to ask for recommendations and directions. For the life of me I don’t understand it. Perhaps it is just random.

Checking into a hotel after a long day of driving, Geri would frequently ask the desk clerk for restaurant recommendations. Why? These clerks tended to be very pleasant young people working at a minimum wage job and whose life experiences and bank account balances probably did not provide for dining in nice restaurants. Predictably, Geri’s question would evoke responses that typically included a short list of favorite drive-thru restaurants–frequently punctuated with menu highlights. (“The strawberry milkshake is to die for!”)

“Of course, if you’re looking for something fancy,” they’d say, my hopes rising in expectation, “there’s always Sizzler.” Oh.

And how does one know who to ask for directions? You can’t be sure that you’re not asking another tourist who may be as lost as you.

In New York I found great fun in mis-directing people. While you may think that was a mean thing to do, I believe that I was adding value to their visit by, for instance, sending them to Greenwich Village despite their having asked directions to Rockefeller Center. After all, the West Village, with its web-like maze of funny streets with curious shops, bars and restaurants, was far more entertaining than a big office building in Midtown–with or without the Rockettes.

My amusement, of course, was mostly imagined in that I never saw the results of my deeds. And it was a safe amusement because there would be zero chance of running into those people ever again.

In Montana, one can’t really get away with such shenanigans because it is very likely you will see your victims later.

Tourism is a large and vital part of Montana’s economy, accounting for $3.4 billion in annual revenues. According to the Institute for Tourism and Recreation, one-in-nine Montanans is employed in businesses supported to some extent by out-of-state dollars. More than half of the annual revenues are earned from the sale of fuel, food/beverages, and lodging. The residents of the Treasure State could benefit greatly from a sales tax, but that’s another story.

There is a long history of tourism in Montana. Just thirteen years after Custer took his last breath at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 the Montana Lodging and Hospitality Association was formed. While it’s not clear exactly what the association did back then (or does now, as far as that goes), somebody thought such a trade lobby was important.

What might be more important would be to form an association to help tourists navigate the vagaries and pitfalls awaiting people on vacation. While many of the missteps of some of these temporary vagabonds are indeed humorous to observe, they lead to my wondering if they have this much trouble on holiday what must their everyday lives be like.

The misconceptions about Montana are perhaps what attracts so many to our borders. For the record, few of us live in log cabins or tepees. We have countless miles of paved roads, but dirt roads are easy to find. Most of us walk around unarmed. Traffic signals here carry the same meaning as they do wherever you’re from, unless you’re from Italy. Few of us own cattle. Cowboys spend more time on ATVs than on horseback. Most restaurants offer gluten-free and vegan options. Few of our art galleries offer paintings of bugling elk. We have as many television channels as you do. We have cellphones, the Internet, ATMs and indoor plumbing.

Montana is Big Sky Country and it is a spectacularly beautiful place. We are blessed with a landscape of rugged mountains, mesmerizing high plains, pristine alpine lakes and innumerable rivers that run through it. Our bookends are Glacier National Park in the north and Yellowstone in the south. There is abundant wildlife that should be viewed with great awe and never bothered. Montanans tend to be a friendly lot and most of us won’t purposely give you bad directions.

If the idea of a “big sky” seems foreign or nonsensical, you should come up and see it for yourself.

Don’t forget your cowboy hat.

Photography by Courtney A. Liska