From the “leave well enough alone” department comes a report from the BBC that remarkably doesn’t even mention the Royal Family, the world’s wealthiest clan of welfare recipients whose every clink of a teacup gets the kind of press coverage and scrutiny usually reserved for nuclear disarmament talks and economic summits.

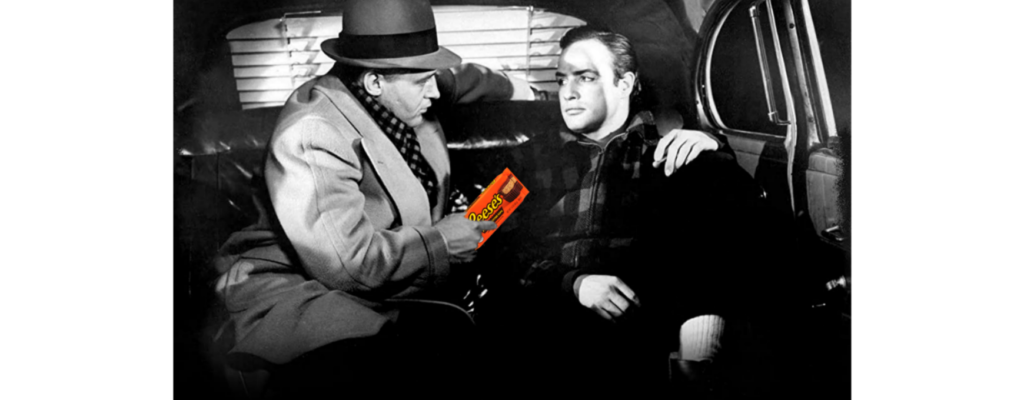

The report details the efforts of Stephan Beringer, chief executive of Mirriad, a U.K. advertising company, to digitally alter film and video to insert product images that weren’t there before.

Product placement is nothing new, dating back to the earliest days of film-making. Companies pay big fees to the film studios to make sure that their brands are seen by moviegoers. Stars wear designer clothing because if some actor is seen wearing DKNY products, some viewers will run out and buy the same to emulate their screen idols.

Or so the thinking is. There is no doubt that movies are an effective way of influencing behavior. In Adam’s Rib, directed by George Cukor in 1949 for MGM, Amanda (Katharine Hepburn) and her husband Adam (Spencer Tracy) are preparing dinner together in the kitchen, and while it’s cooking, they share a grapefruit. It was a slight reference to a fad diet at the time that experts described as “nonsensical, irrational and even dangerous.” Nonetheless, grapefruit sales soared nationwide.

What is behind this new movement to add advertisements to old movies and television shows is a flexing of technological muscle and, lest we forget, greed. It only makes sense that an advertising company would be leading the way to the well promising such riches.

Imagine the possibilities. The next time you watch Casablanca, An Affair to Remember or It’s a Wonderful Life, you might notice signage or re-labeling. Finally, that dull brick wall behind Lee Marvin’s drunken character astride a horse in Cat Ballou, could be used to host a billboard advertisement for any number of consumer products.

The situation speaks to the intent of the filmmaker and his or her integrity in creating a product of artistic merit. There are probably legal ramifications as well, most likely for infringements of copyrights, trademarks, and ownership.

Back in the mid-80s, I was an editor at The Hollywood Reporter, the entertainment industry trade paper, when the relatively new technology of colorization was being widely touted. Producer Hal Roach and mogul Ted Turner were key figures in efforts to add color to black-and-white movies. They, of course, wanted to find new revenue streams by enticing audiences to see old films in a new light.

There was no shortage of detractors who complained that the process was crude, at best, and that lighting designed for black-and-white photography would not be effective in color.

Those opposed to the colorization process included film critic Roger Ebert, Jimmy Stewart, John Huston, George Lucas and Woody Allen.

“They arrest people who spray subway cars, they lock up people who attack paintings and sculptures in museums, and adding color to black-and-white films, even if it’s only to the tape shown on TV or sold in stores, is vandalism nonetheless,” Ebert said.

“What was so wrong about black-and-white movies in the first place?” he asked. “By filming in black-and-white, movies can sometimes be more dreamlike and elegant and stylized and mysterious. They can add a whole additional dimension to reality, while color sometimes just supplies additional unnecessary information.”

At issue was the original intent of the filmmaker, which in many cases could never be known. Would Frank Capra, for instance, have made It Happened One Night (1934) in color had it been an option? I doubt that Elia Kazan could have more effectively captured the gritty essence of New York’s shipping docks in On the Waterfront, his 1954 masterpiece, had it been filmed in Technicolor. And color photography could no more have added to the intensity that Sidney Lumet built into 12 Angry Men (1957) than if he had included a car chase with Steve McQueen at the wheel.

Woody Allen’s opposition was notable, not to mention ironic, in that his first major film was What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, a 1966 effort (in black-and-white) in which he took an existing Japanese spy movie, International Secret Police: Key of Keys, re-edited it and overdubbed existing dialogue with a new script. The result was a chaotic spoof on secret-agent films with a plot involving a farcical search for the world’s best egg salad recipe. It hardly recognized the integrity of the original movie or its director.

The technology of colorization merely added color to an existing product. There was nothing being sold other than the product itself; no McLuhanesque subliminal message of 7-Up where there was none.

The latest technological development comes at a time when product placement is becoming increasingly more important to advertisers. Globally, according to a PQ Media study, such advertising rose 15% in value in 2019. The ever-increasing practice of streaming films and TV shows through Netflix and Amazon Prime, which do not have advertisement breaks, gives product placement a way to subtly reach target audiences.

Because musicians and composers have been essentially cut off from making their livings due to streaming services that remove the need to purchase recorded music, many of the MTV generation are finding hope in the new technology. Old videos could be edited and re-mastered to provide advertising platforms that could be tailored to meet any number of demographic profiles. This could provide new life to old videos, perhaps even reaching new generations of listeners while providing older audiences with a sense of nostalgia in the way that hearing an “oldie-but-goodie” on a car radio might.

But unlike commercial radio, in which songs are sandwiched between commercials, videos would have no alternative but to add logos, signage and actual product to create new sources of revenue.

While we may have become inured to the constant bombardment of advertising in myriad forms, I can’t think that redoing the past will offer much benefit. Nor can I imagine that paying audiences would tolerate a quarter of the movie screen devoted to scrolling pop-up ads.

Tonight, the movie industry, which prides itself on its cultural contributions and its commitment to humanitarian causes, will don its designer best to safely gather and pat itself on its collective back in a heartfelt homage to commercial art. Despite their good intentions, it’s only a matter of time before—taking its cue from ESPN—award categories will be sponsored.

“And the nominees for Bank of America’s Best Actor in a Supporting Role are…”

Photo illustration by Courtney A. Liska

Egg Salad Sandwich (deconstructed)

6 large, cage-free Organic Valley eggs

1/4 cup Best Foods mayonnaise

2 teaspoons Grey Poupon Dijon mustard

1-1/2 tsp. fresh lemon juice

1/4 tsp. Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce

1/4 tsp. Morton salt

1/8 tsp. Durkee ground black pepper

1/2 tsp. Domino’s sugar

1/4 cup finely minced celery

3 Tbs. finely sliced scallion

1 Tbs. finely chopped fresh parsley

Place the eggs in a saucepan in a single layer, and fill the pan with enough cold water so that it covers the eggs by about an inch. Bring to a rolling boil over high heat, then remove the pan from the heat, cover, and let stand for 10 minutes.

Drain the water and run cold water over the eggs. Once cooled, allow to sit for ten minutes or so.

In a medium Corning glass bowl, whisk together the mayonnaise, mustard, lemon juice, Worcestershire sauce, salt, pepper, and sugar. Add the celery, scallions, and parsley. Using a Rubbermaid rubber spatula, fold to combine.

To make the sandwiches, slice one egg for each hoagie sandwich roll. Slather both sides of the roll with the dressing, adding lettuce, and slices of tomato and sweet onion if you’d like. Add the slices of egg. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

Good piece. Quite good, in fact. And clever.

Your lede sentence is a packed beauty and your branded egg salad makes for a tasty ending.