At 2:00 a.m. in a part of Baltimore I no longer recall, the rock band I was working with loaded into a Yellow Cab—an old Checker Marathon with fold-down jump seats—and asked the driver where the after-hours action was. Sizing us up as a quintet of hippies in the early ’70s, he told us about a place where the girls “do amazing things.”

It sounded promising to four of us.

We ended up at the Point, Fells Point at water’s edge to be exact, and were let out in front of one of the scores of bars in that waterfront neighborhood that had its origin in the late-1700s; its gentrification would occur in the ‘80s.

There was a barker touting the adult entertainment inside what was a strip club. “No cover! No minimum! You won’t believe what Miss Sheila…”

Baltimore’s waterfront in those days was an odd mix of Colonial brick row houses and abandoned warehouses. Belgian blocks paved the narrow streets and the businesses that lined them sold sea-faring memorabilia, used goods, working-men’s clothing and boots. There were fortune tellers, head shops and tattoo parlors. It was as strange an urban mix as could be imagined.

And it was a seriously dangerous place to be—rife with drug addicts and dealers, small-time criminals, hookers and drunken sailors looking to brawl. It stood as the American equivalent of the storied Marseilles.

Shortly before dawn, and after being quite amazed at Miss Sheila’s rather remarkable talents, we ended up at one of the tattoo parlors. We drew straws, this band who’d had way too much fun. I was to be the last to go, and by the time it was my turn, the sun was up and I was sober.

I passed on the tat.

Jews are not supposed to get tattoos. Maybe. It’s not particularly clear from reading the Torah. Leviticus 19:28 literally translates, “And a cutting for the dead you will not make in your flesh; and writing marks you will not make on you; I am the Lord.” Because that passage is wide open to vast interpretation, I think Jews opted to say, “Schmuck, don’t put ink under your skin.” The idea of tattooed Jews not being allowed burial in a Jewish cemetery is unfounded, although Lenny Bruce’s joke about his tattooed arm is priceless: “Don’t worry–they’ll cut off this arm and bury it in a Catholic cemetery.”

I had an uncle who was a bit of an embarrassment to the family. He had a tattoo. Like him, it was crude and monochromatic. It commemorated his crossing the International Dateline during the Second World War. My father wrote it off because he was Navy; my dad was Army.

Though fascinated by the tattooed men and women who displayed their body art in circus sideshows when I was a kid, I never had any desire to be host to any tattoo. That early morning in Baltimore I remember numbly staring at generic tattoo options displayed on flash sheets that adorned the walls of the parlor’s waiting room. There were hearts, roses, anchors, barbed wire, and cartoon characters.

Today there are some pretty fantastic examples of tattoo artistry. I see them on the arms and legs of people I don’t really know but with whom I have daily interactions. I see them on my daughter, my partner in this blog adventure. She has eleven of them, I overheard her say recently.

Tattoos have become a part of our culture by design, and I am doing my best to buy into an acceptance of something that seems very foreign.

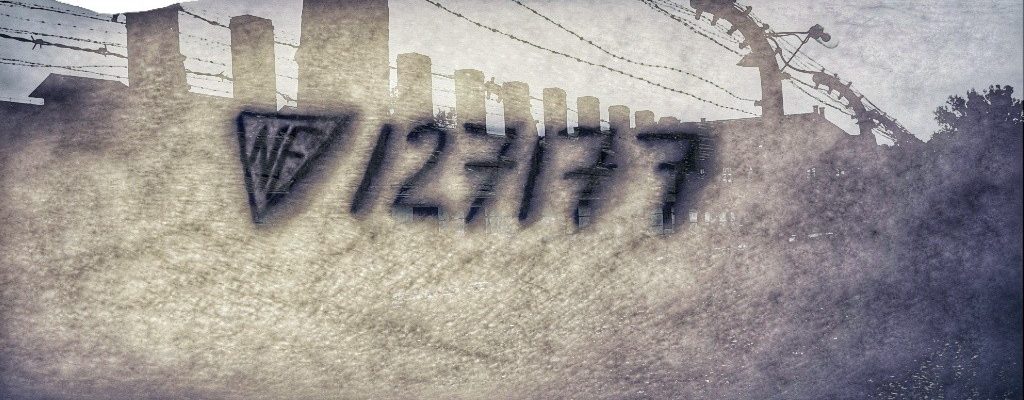

What must have seemed terribly foreign was the act of tattooing that Nazi Germany forced on the prisoners of Auschwitz, the death camp that promised that work would set them free. By tattooing numbers on the prisoners’ forearms, the Nazis attempted to dehumanize people in order to systematically and mechanically exterminate them in a guilt-free manner. Individuals—Jews, Romany, Poles, Czechs, Russians, homosexuals, the physically and mentally infirm—defiled with numbers and devoid of names or personalities. They were not to be related to as members of the human race Hitler aspired to create—the “master” race of blue-eyed blonds.

Although there are those so clumsily ill-informed as to deny that the Holocaust ever happened, there is irrefutable proof of the atrocities committed by criminal Nazis. The unspeakable acts of brutality and barbarism are well documented and photographed. And as hard as it may be to even fathom, it can happen again.

I’ve told this story before but I believe it bears repeating:

“AS HE REACHED FOR THE SALT across the table in a quiet dining room at the Beverly Hills Hotel, the sleeve of his white, French-cuffed linen shirt rose up his arm, revealing the tattoo that had once reduced his name and identity to a number.

“Samuel Pisar recited his haftorah for his bar mitzvah in the winter of 1941 inside an apartment in the Nazi-established Jewish ghetto of Bialystock, Poland, his birthplace. A few months later his father was executed on the street outside their home, and the thirteen-year-old Samuel was transported in a cattle car to Majdanek, the first of six concentration camps he would call home until his escape from a death march headed to Dachau four years later.

“His mother and younger sister were transported elsewhere for extermination.

“His life, detailed in his 1980 book, Of Blood and Hope, was a saga of the nearly unspeakable, of survival and self-recovery. Pisar became an international attorney and diplomat. With earned doctorates from Harvard and the Sorbonne, he served as an adviser to President John F. Kennedy and French president Valery Giscard d’ Estaing, and counted among his friends and clients Artur Rubenstein, Marc Chagall and Elizabeth Tayor.

“He dined at fine restaurants and remembered the ‘gray’ bread they ate for sustenance in the camps.

“He told me over the course of our 1980 lunch that ‘the gnawing starvation that sucks the will out of two-thirds of mankind and subjects whole continents to political and social convulsions is no abstraction to one like me.’

“In measured language he expressed concern that ‘well-meaning but desperate majorities [could be tempted] to surrender political power to totalitarian leaders.’

“Effective leadership is what is desired by the electorate, he said, noting that ‘effective’ is not necessarily a shared value.

“’That’s something that is not understood about Hitler. He was not just a wild man who took over. He was man who offered solutions to the people and was elected to office.’”

It is unlikely that any survivors of the Holocaust will be alive in just ten years. There are countless polls and studies that show denial and gross misinformation about and misunderstanding of the events preceding and during World War II. As the survivors disappear, many of their stories will disappear with them, and without a collective memory the likelihood of a repetition of this most sordid crime increases.

The story must survive. The Shoah (Hebrew for “catastrophe”) must inform our behavior as we move forward as a society.

We are duty-bound to never forget.

Balancing the courage to listen to people tell their stories with characterizations that might trivialize the inherent evil of Nazism is approached with a certain trepidation. While there is no shortage of films and documentaries, books and articles, conversation will continue to best personalize the stories that need telling.

Sadly, 6 million Jewish stories were taken from us. But some have survived.

Mr. Pisar’s story is one I’ve both read and heard from him. I think his is a story worth repeating and worth remembering.

I’ve chosen to honor his memory (he died in 2015, aged 86) by having the number assigned to him at Auschwitz tattooed on the inside of my left forearm, where his was. I’m hoping it will spark conversations and open doors to an understanding of how capable some are to disregard human dignity and life itself.

The tattooist noted that most people want their first tattoo to be of great significance and import. He was right on both accounts.

It’s a small effort being made from the heart. Never forget.

Photo montage by Courtney A. Liska; Tattoo by Noah Riley

Two reliable sources for Holocaust study online are Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum at http://www.auschwitz.org/en/ and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum at https://www.ushmm.org/. I also found JewishGen to be a great source for genealogy research of Holocaust victims and survivors at https://www.jewishgen.org/new/.

Chicken Stock

Known as Jewish penicillin, chicken soup soothes the soul. It may even be effective in our current crisis. I’m hoping that none of you will be charged to test its efficacy. This recipe is the basis for many soups and sauces. Stay well. Wash your hands. Make soup.

2 pounds chicken backs and necks

2 leeks, white and pale green parts, coarsely chopped

2 carrots, coarsely chopped

1 medium onion, peeled, studded with 2 whole cloves

2 stalks celery, coarsely chopped

2 cloves garlic, unpeeled

8-10 whole peppercorns

Bouquet garni

4-5 sprigs of parsley

2 sprigs of fresh thyme

1 bay leaf

Wash the chicken bones under running water. Blanch the bones in boiling water, 3-4 minutes. Rinse under cold water and reserve.

Place the chicken pieces in a stockpot and cover with four quarts of cold water.

Bring to a boil. Add the other ingredients, bring to a boil and simmer, partially covered, for about two hours. Be sure to skim the fat and foam.

Strain through a fine sieve and let cool. Remove all of the fat (schmaltz) that rises to the surface.

What a beautiful story, Jim, told with your trademark power, depth, sensitivity and color (and the perfect leavening of humor. Your words forth with a heartfelt urgency. Never forget, indeed. You are Mr. Pisar are literally and figuratively brothers in arms, forevermore. A brilliant piece of prose. Mazel tov!

You’re too kind. But what can one expect from the Toilet Paper Fairy?

This brings tears to my eyes and it always will.

I didn’t want to make you cry. Thanks.

If only every human being was “duty-bound to never forget!” As always, Jim, thank you for your passionate voice.

Thank you for your kind words.

Jim, I love your writing. I am reading a book about the Holocaust now, and I have to put it down at times. I never heard a thing about it when a kid, even though I had many Jewish friends and Jewish neighbors. This was in the 50’s and 60’s. I first learned about it in college when a friend told me her whole extended family had been wiped out. I was shocked but also pissed that no one had ever told me about it. Since then, I’ve made a point of studying what happened. I see similarities between Trump and Hitler and Trump’s fanatical supporters who allow him passes on unimaginable behavior and crimes. We must continue to learn about what happened to the victims of the Holocaust, but also do what we can to bring his term to an end. He truly is frightening, and honestly anxiety provoking for me. Thank you for this piece of writing and for your tattoo in solidarity with your friend. May we always remember and never be complicit in it happening again.

Thanks, Annie. I appreciate your sincere interest.

Thank you Jim for this important insight. As democracies struggle to stay afloat amidst so much war-driven migration and such strong political and racial polarization, it is important to remember what can happen – indeed what appears to be happening in way too many places. Transparency in governance, compassion for one another, and remembering the past are important keys to maintaining this fragile experiment in democracy. You were among the first of my deep-thinking & well read friends. So nice to be back in touch and reminded periodically why our friendship blossomed so quickly.

Thank you, Clark. I, too, am glad we’re back in touch. I’m grateful for your friendship.

What a great piece of writing, Jim.

Thanks, David.

A moving story beautifully expressed.

Thank you so much. You, and a very small handful of others, have been a constant inspiration to my life. I cherish my memories and am eternally grateful for lessons learned–on and off the percussion stage.

Thoughtful insights and a moving story; both exquisitely expressed.