The problem with books is they have the ability to upset the status quo, as well as any number of apple carts.

They can be life-altering, transformative. They can feel like magic, world-making and unforgettable. They can be dangerous, upsetting. Many inspire such feelings, especially in young people. Reading is meant to be challenging, and literature should serve as a way to explore ideas that feel unthinkable, unfamiliar, and even illicit. They can challenge lies with truth. They can take you to exotic locales and introduce you to a wide variety of characters from wildly different walks of life. Ideas abound within their pages. Imagery can be fantastic, familiar or gritty. They can expose social ills and suggest their remedies.

And when a notion that provokes deep thoughts dances off the page, you can stop for as long as you wish to ponder such a notion before turning the page. (Try doing that with your devices.)

As ridiculous as it sounds, there are those walking the earth who find no value in any such challenges to intellect or mores. They don’t care to be challenged by ideas or differing points of view. And some of them want to make sure that their children—and yours—cannot access such information.

It’s safe to suggest that there have been very few libraries or schools that have not suffered the slings and arrows of the repressive forces wishing to suppress books that they find offensive.

It’s probably also safe to suggest that the oppressors have not read the books they want banned.

Ulysses, by the Irish author James Joyce, jumps to mind. Its nearly impenetrable prose keeps most would-be readers from even getting as far as the masturbation references in the “Nausicaa” chapter. The book was banned in the 1930s in both the UK and the US. And as far as masturbation goes, one does not have to read about it to adopt and understand its pleasures.

The Tropic of Cancer is in that same league. Henry Miller wrote frankly about sexuality in a novel that a Pennsylvania judge found to be an “open sewer, a pit of putrefaction, a slimy gathering of all that is rotten in the debris of human depravity.” (Note to self: It’s been on the shelf for forty years. Read it.)

And then there’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the D.H. Lawrence novel that led the prosecution in a 1960 trial to ask if you would “wish your wife or servants to read it.” The book sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

Politics, sex and prejudice—sometimes all three in a not-so tidy package—lead the reasons for people not to read.

Huh?

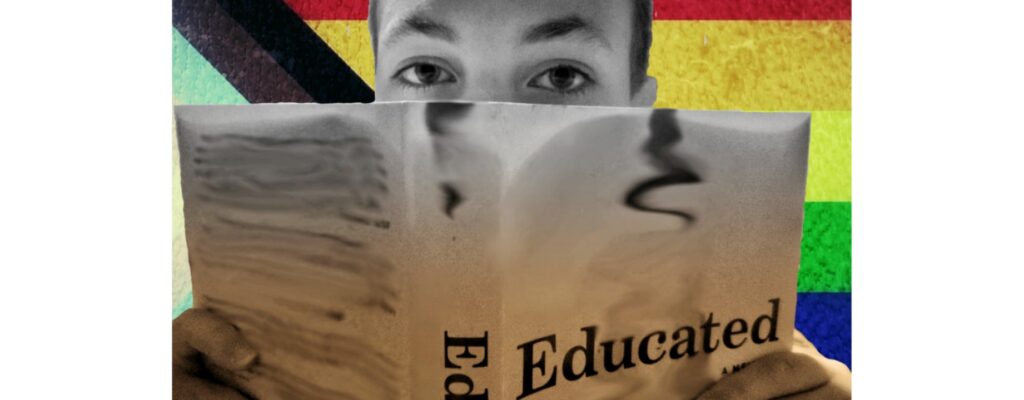

The current anti-book climate seems focused on tomes exploring the LGBTQ culture. I can’t figure out what the problem is, even if there are explicit passages that, ultimately, explore an expression of love.

Note to the homophobic: If you read a book about a gay person, it doesn’t turn you into a gay person. It’s not an owner’s manual offering tricks, procedures, or techniques. Similarly, if you read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, it doesn’t make you want to find a family of four in Kansas to kill.

The LGBTQ book leads to an understanding of that community. Capote’s leads to an understanding of murder.

There’s a Republican in the Texas House of Representatives named Matt Krause. He has busied himself searching in public school libraries for any books that might generate “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of [a student’s] race or sex.” In October, he distributed a watch list of 850 books.

Besides being something of a paranoid idiot, he is denying exactly what books are meant to do. Most students are resilient enough to take “discomfort, guilt, anguish” etc. in stride. In most cases, knowledge makes the students think, not act. Although some should.

My daughter gifted me How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi. It is a thought-provoking book that explores the disturbing aspects of racism. It suggests that being non-racist is not enough. One needs to be anti-racist. It’s on Krause’s short list of books to be banned, as are Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and John Irving’s The Cider House Rules.

Ironically, The Year They Burned the Books by Nancy Garden made a haphazard list that included a Michael Crichton thriller and the Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine.

Whether it was a scandalous story of sex or simply taking issue with a talking pig (Animal Farm by George Orwell), many people have found reasons to ban some of the world’s best and most famous books. Court cases have been fought, books have been burned, and fatwas have been issued.

One of the most banned books is Brave New World, Aldous Huxley’s cautionary tale of a world grown too used to artificial comfort built on exploitation, and for what they saw as its comments against religion and the traditional family, as well as its uses of strong language.

The history of World War I was brought into sharp focus in All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque. Seen as unpatriotic by the National Socialists and even a number of non-Nazi aligned military personnel and writers, what these groups and individuals disliked about the book is exactly what makes it so compelling an account of the true horrors of warfare.

On the home front, The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s moving depiction of migrant workers in the Dust Bowl, was found to be so brutal that it was widely banned, despite its truthful accounting of the Depression.

Frequently, the truth hurts.

To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee, The Color Purple, by Alice Walker, and Beloved, by Toni Morrison, have been the targets of book bans for their content about race. Richard Wright and James Baldwin have also suffered such indignities.

My advice to anybody who learns the title of a book being banned or censored is to run out and get a copy before it’s too late.

As Isaac Asimov once noted: “Any book worth banning is a book worth reading.”

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

Papa’s Soup

This recipe comes from a late afternoon throw-together of whatever happened to be on hand. We liked it!

6 cups water

Salt

3 Tbs. olive oil

2 leeks, sliced

2 medium potatoes, peeled and chopped

1/2 lb. carrots, peeled and chopped

2 large celery stalks, chopped

1 large onion, chopped

2 garlic cloves, minced

White pepper

Plus, one large carrot (diced), one stalk celery (diced), one can (15 oz.) small white beans, drained.

Bring water, salt and oil to a boil, adding the vegetables in any order. Cook at a quick simmer for 45 minutes. Purée. Sauté the diced carrot and celery in olive oil. Add to puréed soup, along with beans.