Twice each year during my grade school years, I would join my classmates for a trip into the future.

With sack lunches in hand, we’d load into a yellow bus and travel the short distance to the Museum of Science and Industry in Jackson Park, a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. Housed in what had been the Palace of Fine Arts from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the museum was endowed by Julius Rosenwald, the Sears, Roebuck and Company president and philanthropist. Supported by the Commercial Club of Chicago, it opened in 1933 during the Century of Progress Exposition.

That was only twenty-odd years before my curiosity was being piqued by the displays of mankind’s achievements in science and industry.

The takeaway from those field trips was that the future would be fantastical, full of weird and wonderful devices that would change our lives. It was barely imaginable. Every exhibit was hailed as the Future of whatever…kitchen, bath, etc. We got a glimpse of what automobiles, trains and planes might look like.

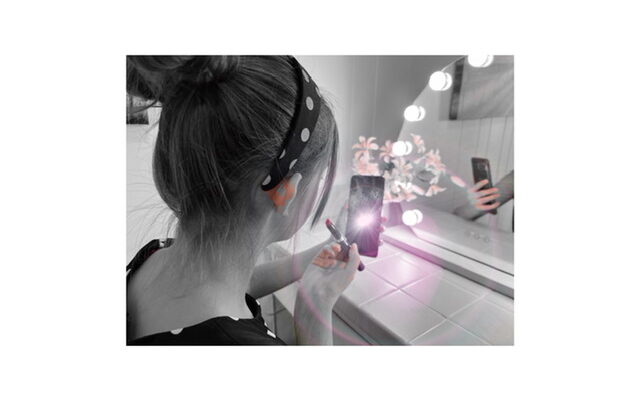

One brief peek into the imagined future that I remember was a demonstration of a telephone that had a visual component. In those days before we had yet to see anything beyond a rotary phone, this contraption, the name of which I can’t recall, allowed a two-way communication of both audio and visual. You could actually see whoever it was you were talking to. (In his 1968 song, “Younger Generation,” John Sebastian made a reference to a “videophone.”)

My mother, who accompanied my class on this particular trip, was appalled at this cumbersome device, noting that she would have to put on her makeup before answering the telephone. She was, in short, opposed to progress on that level.

The promise (threat?) of having telephones being portable was only a few years down that early road. Now, of course, Zoom meetings, spurred by the Corona-19 virus, have replaced having to be present in the course of doing business. There are several other competitors in that burgeoning field, not all of which are compatible with just any device. My smartphone is smarter than me.

On my desk, I have my computer, an iPad, and a cellular telephone. Each device allows me to do different things, from research to amusement, video-conferencing to simple conversations. My phone goes with me always. I remember when my desk had a typewriter, a fax machine, and a telephone that was actually plugged into a wall.

None of the above were portable.

The way we get news and information has been changed dramatically. I grew up with newspapers and radio. (We got our first television on the day of JFK’s assassination.) The Sun-Times adorned our breakfast table. On the pages of that paper was everything one could hope for: entertainment, world and local news, op-eds, feature stories and a weekly food section. One’s fingers would darken from the ink while reading it.

Our research was done at the library, where we could also check out books.

Today’s e-books I find to be a poor substitute for the books I want to read. I like to hold books, just like I prefer a newspaper to a video feed.

Sadly, newspapers are shutting down operations from coast to coast. Those that remain are smaller and many have cut back on the number of publication days. They generally have more wire service stories than locally produced news.

Of course, television offers an immediacy that can be overwhelming. When the effect of 9/11 was first compared to the attack on Pearl Harbor, my mother noted that one saw the newsreels of Pearl Harbor and that was that. Few could know how many times one saw the video of the planes crashing into the twin towers. Today, we’re being fed continuous tape loops of the action in Ukraine. A sense of urgency to not miss something of significance keeps many of us glued to our screens.

And what will the future hold for ways to stay informed? What will replace what? There is, after all, a replacement for everything.

A wire story I read last week told the story of the demise of Kmart. There are only four stores left, the story reported—down from 2,400.

Sebastian Spering Kresge (1867 – 1966) was an American businessman who created and owned two chains of department stores: the S. S. Kresge Company, one of the 20th century’s largest discount retail organizations, and the Kresge-Newark traditional department store chain.

The first Kmart opened in 1962 in Garden City, Michigan. In 1977, the S. S. Kresge Corporation changed its name to the Kmart Corporation. In 2005, Sears Holdings Corporation became the parent of Kmart and Sears, after Kmart bought Sears, and formed the new parent company.

Sears, founded in 1892, is a retail operation that sells everything from tools and appliances to clothing and household furnishings. It had begun as a mail-order operation that made big city goods accessible to rural America. Throughout the 1980s, Sears was the largest retailer in the nation.

Both Kmart and Sears put several small retail operations out of business. Boutiques, shops, and hardware stores suffered, with the larger operations replacing the small with discount pricing and vast selections of goods.

The emergence of Walmart and Target on the retail scene cut deeply into other businesses, again with the behemoths trouncing on the local stores. Their wholesale buying power allowed them unmatched market share.

So what will replace Walmart and Target in the future? Amazon, buffeted by the pandemic, will be replaced by God-only-knows. It seems that goods from every retail outlet can be found on the internet, including the retail giants.

Clearly the brick-and-mortar operations will continue to suffer.

But I’m old fashioned. I like to touch those things I wish to buy. I want to make sure that clothing will fit me. I want to pick the vegetables and meats I’ll prepare. And I want to support those little shops whose revenues help sponsor the community in which I live.

I’d also like to talk on the telephone only when I’m at home.

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

Five-Bean Casserole

1/2 pound bacon, chopped

2 cups onion, coarsely chopped

2-3 cloves garlic, minced

1/2 cup packed brown sugar

1 teaspoon mustard powder

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup cider vinegar

1 (15 ounce) can butter beans, drained

1 (15 ounce) can great northern beans, drained

1 (15 ounce) can kidney beans, drained

1 (15 ounce) can pinto beans, drained

1 (15 ounce) can baked beans

Heat oven to 350 degrees.

Sauté bacon over medium-high heat in a deep pot and cook until evenly browned. Drain and set aside.

Sauté onion in bacon fat over medium-low heat until soft (5-6 minutes); add garlic and cook another minute or so. Add the brown sugar, mustard, salt, and vinegar. Cook covered on low heat for 20 minutes.

In a four-quart baking dish, combine the bacon, onion mixture and beans. Mix well, and bake covered for 1 hour. Uncover and bake another 10-15 minutes.