In 1999, as I was first sticking my big toe into the icy waters of the restaurant business, I read an oddly amusing and rather frightening story in the New Yorker titled “Don’t Eat Before Reading This.” It was written by Anthony Bourdain, a New York chef few people had ever heard of, even if one had eaten at Brasserie Les Halles in Manhattan where he had cooked and served as executive chef for many years.

A year later, he published Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly (HarperCollins). The book spirited him out of the kitchen and he was quickly on his way to becoming one of the first so-called celebrity chefs with his own show on the relatively new Food Network. That first show, A Cook’s Tour, did not feature him demonstrating how to make omelets or assemble bœuf à la Bourguignonne, however. Nor did his subsequent No Reservations on the Travel Channel or Parts Unknown on CNN.

He was the chef who ate.

Each of his shows served to bring unfamiliar worlds to his viewers, along with their various culinary traditions. Each episode was studded with cultural notes that demanded both attention and respect. Bourdain traveled to more than eighty countries insisting along the way that we would be better people should we get to know, appreciate and accept other people, their ideas and habits.

He thought we should eat each others’ food, and he believed that building bridges rather than walls was the wiser choice.

Bourdain was smitten with the little town I’ve called home for twenty-five years now and I met him only briefly during one of his visits here. It was a meeting of little consequence, but he seemed pleasant enough as we chatted for a minute or three about the physical beauty of Montana. The canyons of his home, after all, were constructed of concrete, steel and glass. We chuckled about our appreciation for each other’s environments. He longed for Montana; I still missed New York.

While few of us will ever have the opportunity to travel to eighty countries and eat snakes and locusts, eyeballs, spleens and goat testicles with native peoples, we might do well to emulate Bourdain’s sense of how food can bring us closer just by looking to our own culinary traditions that have been poured from the melting pot of our nation of immigrants.

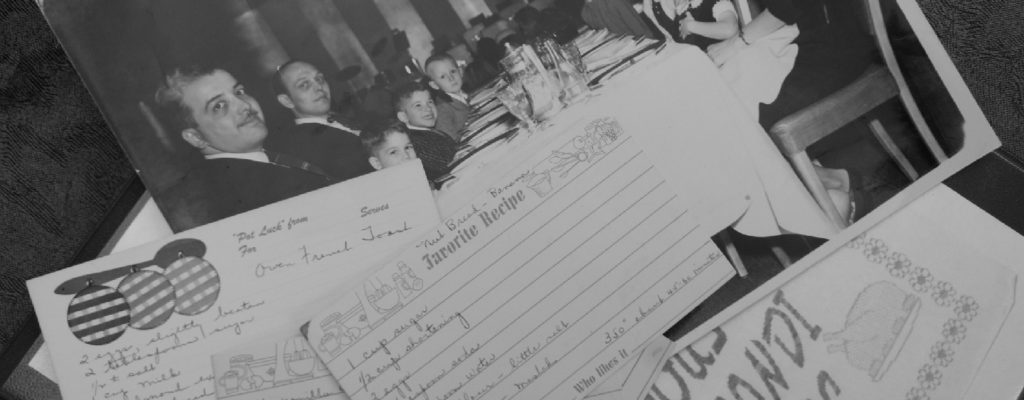

A few weeks ago in my “Growing Up Italian” post (April 8, 2018), I mentioned that I had received a few hand-written recipes that my Aunt Grace Interlandi had taken from the notes she made cooking with Grandma. It was fun to read those–each evoking childhood memories and making me wish I could enjoy those dishes again in the company of my “cousins.”

Just a week or so later, I received a copy of “The 1991 Reunion Cookbook–Famous Interlandi Recipes.” It is a fifty-eight-recipe, fourteen-page trip down memory lane, full of recipes remembered and interpreted by members of the Interlandi family. Everybody in that family knew the basics of cooking and therefore the recipes are almost completely void of measured detail, namely, times and ingredients. Instinct rules.

Cousin Gia’s recipe for borscht (an odd inclusion in what is basically an Italian-American collection) says to “boil a bunch of beets and peel.” Then, “fry a cabbage and some onions in butter until soft.” It continues: “Put four cubes of beef bouillon, bay leaf, dill, lemon juice, white vinegar (2 tsp.), white wine, pepper to taste in pan with cabbage. Pulverize the whole thing and taste. Serve with [a] glob of sour cream.”

I presume that at some point the beets should be added to the mix, although it doesn’t say that.

I believe this is one of the best recipes I have ever read if only for the challenge it presents to the cook due to its lack of detail. Why the beef bouillon and white vinegar are the only ingredients with specified amounts is a mystery. How many beets constitute a bunch? How long must one fry a cabbage of indeterminate size and some onions before they are ready to be “pulverized”?

I have housed this treasured family collection in a three-ring binder for safe keeping, reference and easy reading. It was printed on a dot-matrix printer, its cover decorated with a floral border and clip-art turkeys. The recipes are good, the evocation of memories are better. It is within an arm’s reach of my desk.

I PROBABLY SPEND TOO MUCH TIME thinking or, if you will, obsessing about food, reading about food, and putzing around in the kitchen playing with food. There are few things that interest me more. Oddly enough though, many of my fondest food memories have more to do with the company, the circumstance and the atmosphere than whatever it was that happened to appear on my plate. I think that might be true for most of us.

As I’ve noted before, my mother was not an accomplished cook. She loved to cook but she had no culinary imagination, few kitchen skills and little confidence in front of the stove. Her successes were few. I will never know what joy she could possibly have found in her quest. As a young girl in Nebraska, she was tasked with turning the family’s leftovers into soups that were ladled out to the homeless men who wandered through town in search of employment during the Great Depression. There were no recipes for her soups then, and many of the soups she improvised as a wife and mother were quite good.

But she sought something else and she diligently re-created the recipes she found in magazines. To that end she rendered meals that had a disturbing, Midwestern sameness. Redbook, both the cookbook and the magazine, contributed to the burgeoning culinary homogeneity of the post-War era. And Redbook, along with a handful of other magazines geared to creating a vision of the new American homemaker, was her inspiration, such as it were, and her guide. A blessing that arose from this was that nobody ever liked anything enough to warrant her making it again. She could take a hint, at least. With a steady stream of new dishes for her to conquer there always remained a glimmer of hope for something tasty but no opportunity for tradition.

We had no family favorites, although Mom did make wonderful Yorkshire pudding to accompany our annual standing rib roast on Christmas. In the fall, when bird-hunting neighbors would share their bounty of pheasant, she would simply bread and fry the pieces and serve them with green beans with almonds and roasted potatoes. I’ve had pheasant prepared a dozen ways, but none better than hers.

I have a very few recipes from Mom–hand-written on decorated index cards. One is Grandma Interlandi’s cheese cake. Another is for banana nut bread. Yet another for kolacky–a Bohemian cookie–which she got from Grandma Liska. I treasure them. I like gazing at her meticulous handwriting; I appreciate the effort she made in writing them out for me. The mere sight of them makes me smile.

The winter holiday season is fast approaching and I’d suggest that, if you haven’t already done so, you create a family cookbook and distribute copies of it to your family as gifts. It doesn’t have to be too big or very original. It needs only to remind the family of your own culinary traditions, the dishes you all enjoyed as the scrape and clink of utensils against china provided the soundtrack for sharing your lives over supper.

Being reminded of the ground beef with mushroom soup and egg noodles is more important as a memory of familial warmth and comfort than a recipe. Your take on mac-and-cheese is the one your kids probably still talk about and remember as the best they’d ever had. And almost nobody’s meatloaf can top Mom’s or Grandma’s. Share the secrets of your fried chicken or pot roast, your mashed potatoes, Sunday gravy, or the enchiladas that became a not-to-be-missed Thursday night tradition.

Type out (or better yet, hand-write) a few of those favorite recipes and maybe include little stories about them. Recall the burned roasts, the collapsed souffle, the omelets that just would not fold, the liver-and-onions nobody would eat, the Thanksgiving meal that was served five hours late. Print these precious memories on some nice stationery and bind them into a handsome folder.

You will be thanked with smiles and hugs.

Turkey Tetrazzini

This dish has long been a family favorite and what we always have enjoyed on the days after Thanksgiving and Christmas. It has a widely disputed origin, but I like the the version that credits Auguste Escoffier, the great French master chef, with creating the dish for the pasta-loving opera diva, Luisa Tetrazzini.

1/2 roasted turkey breast (about 4 cups), cut into bite-size pieces

8 oz. crimini mushrooms

2 large onions, thinly sliced

8 oz. spaghetti, cooked al dente

1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese

2 Tbs. cream sherry

8 Tbs. butter, divided

1/3 cup flour

1-1/2 cups whole milk, at room temperature

Heat oven to 400°. Butter a 9×13 casserole.

Heat 4 Tbs. butter in a skillet and sauté the onions until soft. Add mushrooms and continue to cook for about 10 minutes. Add sherry.

In another large skillet, melt 4 Tbs. butter over medium-high heat; add 1/3 cup of flour and whisk, making a roux. Slowly add 1-1/2 cups of whole milk, whisking to make a creamy béchamel.

Add turkey, onions, mushrooms, cheese and spaghetti to the béchamel, mixing gently.

Pour into casserole, sprinkle lightly with paprika and bake, covered, for 25-30 minutes. Uncover and bake another 5 minutes. Let rest for at least 10 minutes before serving.

Photo montage by Courtney A. Liska

Thank you for suggesting I read this. I identified strongly with your mother. Both of my son’s are excellent at conjuring up imaginative dishes. My youngest, Taylor, loves to entertain friends with food. He has recently moved from the London area to Barcelona, Spain. He is in heaven, besides the sunshine, he is raving about the food.

I will definitely be coming back to read your blogs, thank you.