In 1967 I arrived at Interlochen Arts Academy, a kind of concentration camp for teenagers with artistic tendencies and temperaments in northern Michigan, to complete my high school education. I had brought my sticks, mallets, cymbals and a favorite snare drum, a handsome shelf of books (many of which had been penned by Herman Hesse, who was very popular with tortured teenagers back then), a modest Tandy Radio Shack stereo, some jazz LPs, my baseball glove, a Dopp kit with a Gillette safety razor for which I would have no legitimate use during my entire two-year tenure there, and a steam iron.

I checked into a dormitory that smelled really bad—a bit like a locker room, but with deeper, more layered and aged levels of rancidity and stench. We were issued uniforms and nodded assent to assure the guards that we would launder them.

Out of habit, mother-inspired guilt (as if there might be another kind), and a highly developed sense of smell, I dutifully did my laundry but learned from a senior, a kid who I remember as being really tall and who sat on the washing machine while it washed his clothes (he was either protecting his laundry from theft or enjoying the spin cycle in a peculiar way), to wear sweaters to avoid ironing altogether.

My iron, still in its box, stood proudly untouched on the floor of my closet, next to a gallon jug of Mott’s apple cider to which I had added sugar and a handful of raisins in an attempt to make Calvados.

I took that virgin iron—virgin in that it had yet to be used—to Cleveland, the city affectionately known as the Mistake-by-the-Lake and where, upon my arrival in the late summer of 1969, its Cuyahoga River happened to catch on fire. Having just turned eighteen and not at all well versed in things scientific (the academic curricula at Interlochen was a bit light on things like math and science, but we did read a lot of fiction) I had not realized that water was flammable.

“Don’t they use water to put fires out?” I asked my father as we unpacked the car. Dad gave me a look that indicated I should shut up. I pressed on. “Do all rivers burn?”

Having graduated from Interlochen without yet knowing if I wanted to make my way in the world by stringing random words together to form sentences or to stand tuxedoed in the back of an orchestra counting measures until it was time to strike a triangle (clearly, Satan perched on each shoulder), I arrived at Baldwin-Wallace College where, according to Judith Lindenau (my Interlochen English literature teacher and one of my life’s early mentors), I would have access to both a wonderful English department and a music department that rivaled those great conservatories that only taught English as a second language.

My first attempt at college was fun. It probably wasn’t designed to be by whoever it is that decides what the college experience is meant to be, but what the hell.

No doubt motivated by a desire to annoy my father and confound my mother, I declared myself a philosophy major (I enthusiastically embraced the ontological arguments of God’s existence in 13th Century Italy, while embracing existentialism), enrolled in a couple of English classes (Joyce? Lawrence? Mann? Sartre? Huxley? Seriously? I read that stuff in high school, I advised the professor who didn’t seem to care), studied criminal sociology from a guy who actively promoted open-season on feral dogs in neighboring Indiana, took a couple of music courses I thought I could have taught better, and got relief from the college dorm experience by setting afire a trail of Ronsonol lighter fluid that erupted into a small bonfire at the feet of the elderly dorm mother as she exited her apartment to go to dinner one evening.

Timing is everything in comedy and pyrotechnics.

In the meantime, I had convinced my father that philosophy majors weren’t necessarily those bearded folks clad in robes and sandals who stood on street corners with signs warning of the earth’s end. Most philosophy majors, I assured him, drove cabs.

CLEARLY, I WAS EMBARKING ON A SOMEWHAT silly life, but I did my part as a long-haired hippie agitator to help end the Vietnam war by attending countless demonstrations, marches and sit-ins—most of which had pretty good bands, a certain air about them if you know what I mean, and an abundance of bra-less women. Most of my efforts to end the war were aimed at insisting that the college shut down, for reasons that remain fairly unclear to me, but which it did in the Spring of 1970. Vague mission accomplished.

The Dean of Baldwin-Wallace College was a man I liked, admired and respected, and he liked me enough to be so concerned about my future happiness that he suggested I might want to seek it somewhere else. I, of course, had beat him to that punch by having already joined a rock ‘n’ roll band that would not only stop the War, end every imaginable form of injustice and forever change the world, but earn me untold riches—the only manner in which capitalism seemed acceptable at the time. At last, my love of music and literature would meet! My future was obvious: I would write lyrics about the travesties of life, especially those foisted upon us by an older generation, and set them to melodies that would verily float over the three chords and a relentlessly pounding beat that were the hallmarks of pop music at the time.

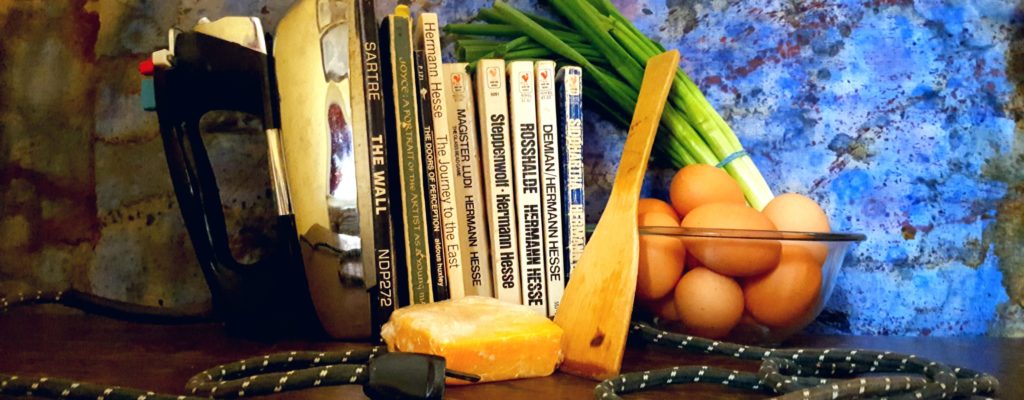

After college and I quit each other, my father wished me something along the lines of “good luck” and I moved into an oh-so-slightly converted hay loft over a multi-use barn that cost $12.50 a week. It had running water, a flush toilet and an aroma that made me long for my dorm room at Interlochen. It had no kitchen and I, an aspiring (read: starving) rock ‘n’ roll musician who loved food and found it a necessary indulgence, had no money to spend at restaurants. Using some of my favorite books from high school, I positioned the virgin steam iron upside down between them, fashioned a pan out of aluminum foil, and proceeded to make a plate of eggs, scallions and cheese.

This is how I prepared one or two meals a day—of eggs, scallions and cheese—for several weeks until one day when I carelessly punctured the aluminum foil and the little steam holes of my iron-cum-hotplate filled with eggs, rendering it useless.

My future seemed grim. I was a college drop-out in a rock ‘n’ roll band, I was hungry, and my shirts were wrinkled.

Scrambled Eggs

Eggs frequently appear at the top of the American day, when life is at its most hectic and hurried, except on weekends when we have plenty of time to prepare breakfast but instead decide to go out to brunch, the most hideous of restaurant meals.

What does this say about us as a species?

It is a mistake to hurry eggs in any of the 100 ways there are to cook them—one for each pleat in a chef’s toque, the legend goes—and cooking them in foil on an up-turned steam iron is ideal actually, provided one doesn’t puncture the foil. Ignore the latest warnings about cooking in foil as we’re all going to die anyway.

All of that having been said, melt a goodly amount of butter over low heat in a small non-stick sauté pan. Do not let the butter brown. Add a tablespoon or two of sliced green onions, a sprinkling of salt, some pepper, and let them soften. In a small bowl, lightly beat two or three eggs with some fresh herbs (tarragon, parsley, chives, chervil) if you’d like, and a tablespoon or two of heavy cream. Add the egg mixture to the pan and stir gently and frequently, if not constantly, with a heat-proof rubber spatula. (This takes some time.) When fluffy curds develop, add a small amount (a teaspoon or so per egg) of your favorite cheese. Keep stirring until the cheese is melted.

Your finished eggs may now be topped with caviar or ketchup or crumbled bacon or shaved truffles or whatever you like. Serve with slices of grilled baguette with butter or olive oil. Sauvignon blanc is a great wine for egg-based breakfasts.

If you aspire to make omelets, I suggest you find any one of the three or four million videos of Jacques Pepin making them on the internet. He’s a charming guy with a great accent and smile, and he knows how to make an omelet.

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

My favorite sentence: “My future seemed grim. I was a college drop-out in a rock ‘n’ roll band, I was hungry, and my shirts were wrinkled.” I think there might be a song in here somewhere!

We lived in Travis City for a time . . . such a beautiful little town on Lake Michigan and so I am quite familiar with Interlochen. However, your description familiarizes it, perhaps, a bit too much!! haha

Whoops, meant to say Traverse City!

“Learn what is to be taken seriously and laugh at the rest.”

Hermann Hesse

Steppenwolf

Love your writing Jim?

So many memories here – most of them fond. Despite the food and uniforms (because of them?) IAA has quite an impact on both of us. My trip to Ohio to see you, Wally, and the band was one of my big college adventures – photos coming soon. Having just recently discovered the quality of your writing I see that my reading list just grew substantially. Thank you dear friend. I look forward to this opportunity. Wonderful work sir!