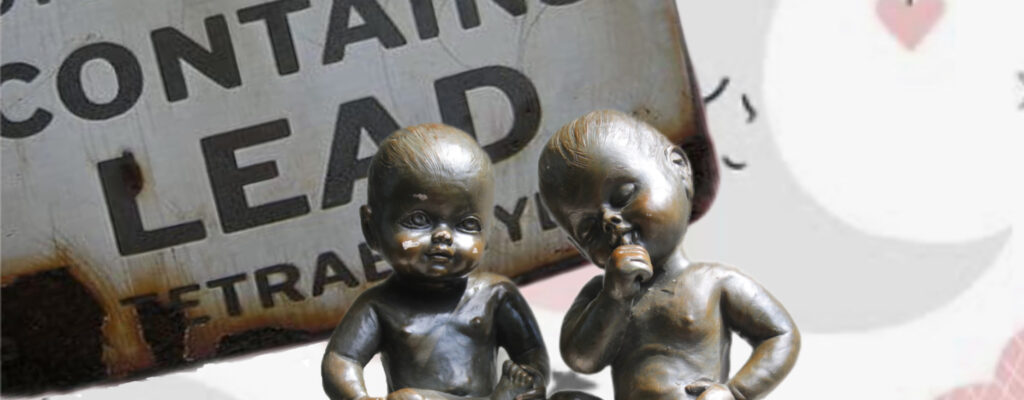

Imagine my surprise one day a couple of weeks ago to learn that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was considering a proposal to set a maximum of the amount of lead found in baby foods.

“Considering?” Wait a minute. “Maximum?”

What the FDA issued was a “draft guidance” which would not be mandatory for food manufacturers to abide by.

That alone reminded me of traffic lights in Italy, which seem optional if you’re riding in a taxi in Rome.

No less a publication than The New York Times issued this grim story lede on January 24: “The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday proposed maximum limits for the amount of lead in baby foods like mashed fruits and vegetables and dry cereals, after years of studies revealed that many processed products contained levels known to pose a risk of neurological and developmental impairment.”

The simple fact is that lead is a neurotoxin, and no amount of it is safe.

We’ve known about this since 1922 when the U.S. Public Health Service warned of the dangers of lead production and leaded fuel. These precautionary warnings went unheeded for more than 50 years.

Those very same dangers were repeated in the use of leaded gasoline until 1973, the year the United States started its withdrawal from leaded gas. That was in conjunction with the development of catalytic converters (leaded gas destroys them) in 1978. By the mid-’80s, most gasoline used in the U.S. was unleaded, although leaded gasoline for passenger cars wasn’t fully banned in the U.S. until 1996. By then, leaded gas was gone from your neighborhood gas station. (Today, leaded fuel can be used only in aircraft and off-road vehicles.)

Within that same time frame, the government addressed the issue of lead in paint. Used to help quickly dry the paint, the additive dates back to paints in the 14th century. Exposure to high levels of lead may cause anemia, weakness, and kidney and brain damage. Studies have also shown a drop in IQ. Very high lead exposure can cause death.

Banned from household paints in 1977, it is still available for some commercial uses, as well as those paints used to paint highway and parking lot stripes. If your house dates before 1978, it is likely that lead is on your walls, just like asbestos is likely to be found in tile and linoleum floors. This is also when the use of lead paint in toys and furniture was banned in the United States.

We’ve long known that the consumption of crumbling paint with lead is a danger to children. Lead is actually sweet tasting, so children, once exposed to it, will continue to enjoy its taste. Consumption, as opposed to mere exposure, also hurries the lead’s effect.

Not remarkably, crumbling wall paint is more likely to appear in homes awash in poverty, thus demonstrating an historical increase among urban Blacks.

Many years ago, my then-teenaged son and I got invited to go snake hunting on a south-facing mountain slope outside of town. The snakes we have in Montana are prairie rattlers, and our hunt did not include any killing. Instead, our leader in this adventure would disturb the sanctity of a snake den with a prod. As the snakes emerged from their rock shelter, he’d pick them up—sometimes two at a time—and then, after having made close eye contact with each of them, he’d playfully toss them at my and my son’s feet. We slowly worked our ways down the hillside until our host mistook a snake den for the home of several skunks, many of which doused our friend with their inimitable scent.

My son just shook his head at this fiasco, no doubt questioning my choice of so-called adult friends.

“Do you think he ate a lot of paint chips as a child?” my son asked.

“Maybe,” I answered, adding, “probably.”

My friend could trace his heritage to Gaelic beginnings. Immigrants to the US in the mid-1800s, they settled in Appalachia, taking up religious practices that included faith healing and snake handling. They also ran successful moonshine operations in the area’s backwoods. It was his history he competed with, beating out only the faith part.

We’ll never know if his Appalachian childhood home had paint peeling from its walls.

The fact that we know about the dangers of lead in fuel and paint, should have been enough to inform us that oral consumption of lead from commercial baby foods might be a bad thing. Babies eat baby food and babies, during this particular time of their lives, are at their most vigorous times of development. Basically, most organs (including the brain) and the entire nervous system are most vulnerable to attack by this insidious poison.

The idea that the FDA is toying around with the health and safety of our children is an abomination.

The FDA should abandon all its subsidized studies and immediately serve each manufacturer with cease-and-desist orders to stop production until they can come into compliance with that “draft guidance.”

IQ points are dropping away with each jar of pureed squash. As a nation, we can’t afford that.

Photo illustration by Courtney A. Liska

Baked Acorn Squash

I was pleasantly surprised to find some acorn squash at my local market last week. This is a wonderful side dish with pork roast or lamb. My favorite topping, added at the end of cooking, is cranberries.

2 medium acorn squash

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil, divided

¼ teaspoon fine salt

Heat the oven to 400° and line a large, rimmed baking sheet with parchment paper.

Cut the squash in half from tip to the stem. Scoop out the seeds and stringy bits inside, and discard.

Place the squash halves cut side up on the parchment-lined pan. Drizzle the olive oil over the squash, and sprinkle with the salt.

Bake until the squash flesh is very easily pierced through by a fork, about 30 to 45 minutes depending on the size of your squash. Add any desired toppings, and serve warm.