Geri spent much of her childhood in Ireland, romping about the lush green pastures of the idyllic Gortnamona, the family farm in County Galway, playing with the lambs and riding the family’s thoroughbred and draft horses over hill and dale. She also was charged with trudging metal buckets of water from the nearby well so Granny could wash the clothing and cook for the family, although one would hope not in that order.

She escaped to America just before her twelfth birthday, which would have been celebrated with tearful goodbyes as she boarded a train to a distant boarding school. There, under the tutelage of nuns, priests and the like, the next six years of her life would have been spent learning to conform to behavior that would allow her entry to an Irish adulthood.

Her father was an Irishman who spent much of his early adulthood trying to salvage his marriage and keep his family together. This entailed an awful lot of trans-Atlantic travel via airplanes and ocean-going liners, leaving from such ports of call as Shannon and Cobh (Queensland), the latter being the very place where some sixty years earlier Leonardo DiCaprio had boarded the ill-fated Titanic.

But that’s beside the point.

Geri had gained early admittance to some boarding school in the West of Ireland and was ready to begin getting her knuckles rapped by a pray of mean nuns when her father—back in New York—heard the news. He flew back to the Auld Sod, grabbed his eldest daughter by her white-gloved hand, along with her two sisters and mother, and returned the family to New York posthaste. There, in Woodhaven, Queens, at the venerable St. Thomas the Apostle, Geri displayed her Irish rearing to the great amusement of her fellow classmates and got her knuckles rapped by yet another pray of nuns.

Geri had been raised to be polite and to conform to the behavioral standards of her Irish forebearers. Raised on a working farm, Geri helped her Granny feed the workers a sumptuous (by Irish standards) noon dinner, served in the field on bone china, with pressed linens, polished silverware and Waterford crystal glassware. She knew to dress in white gloves and frilly dresses, patent-leather shoes and a bonnet befitting the season when she traveled to town. Tea was a formal thing and one dressed for it.

Twelve-year-old boys were sent off to boarding schools as well, the main difference being that priests were in charge of knuckle-rapping, along with other heinous acts.

Things were vastly different in the America in which I was raised. Things were grittier and tougher. The good dishes came out only when there was company coming. We didn’t have any Waterford crystal. On our own, our main eating utensil were five-inch switchblades. (I made up that last part just to sound cooler than I could ever be on my own.)

It was my sister’s refusal to wear white gloves and patent-leather shoes on any occasion that led directly to the threat of her being sent off to finishing school. We didn’t know what that meant, but we figured that it was a girls-only thing because any misbehavior on my part was met with threats of reform school or military academy.

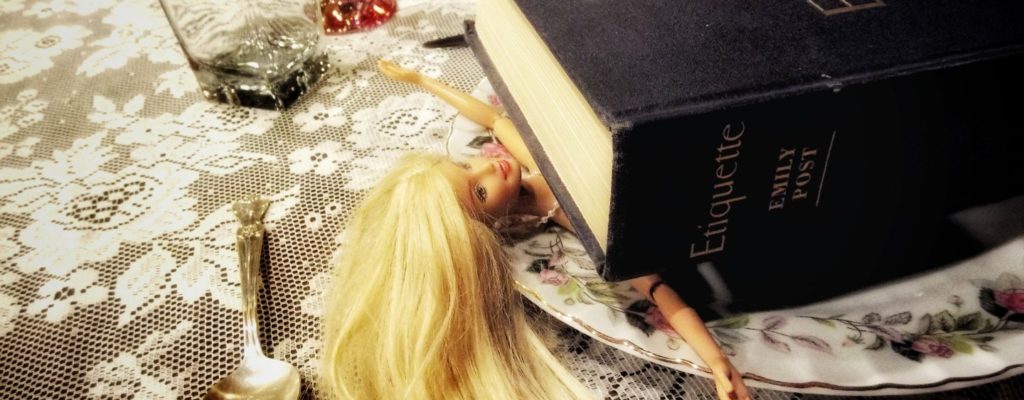

Finishing schools, which are in short supply these days, were places where young girls were magically transformed into young ladies. These transmutations of the female soul took place in the dozens of schools clustered on the upper floors of Wabash Avenue in Chicago’s Loop. One could see from the street girls stiffly walking past the windows with copies of Emily Post’s Etíquette balanced precariously on their heads.

Perhaps in hopes of by-passing some of the classes should my mother’s threat of finishing school ever come to pass, my sister—albeit for a brief time—walked everywhere with Post’s tome on her head.

My mother seemed to be the only household member whose interest in good manners went much beyond not slurping one’s soup. It seemed that Etíquette was always close at hand just in case we had to entertain Europeans who eat their salads after the entree.

We benefited from instructions about dressing properly for any occasion, shortly after patent-leather shoes went out of style. And we were taught the basics of setting a table and which fork to use for which course (start on the outside and work your way in). I was taught to hold doors for people in general, and to stand up when a woman approached the table, unless she was the waitress.

We never learned how to treat servants because we never had any. I remember that we were always nice to Lulu, the woman who cleaned our house on Tuesdays, despite the fact that my mother didn’t think she did a very good job.

My mother annoyed us all with her insistence on our speaking “the King’s English,” a strictly Anglo-Saxon approach that confused my father, whose language skills were those he’d learned from his Eastern European immigrant parents. But she had several other ways to annoy him.

Although the practice of good manners can perhaps be overdone, they seem to me to be a basically good thing because they make one mindful of others. Seeing to someone’s comfort is a nice thing to do. We all pretty much enjoy a compliment. Everybody likes others to be considerate. We don’t like dining with those whose table manners are akin to what one might witness in a barnyard—except in Ireland, where I can only assume the pigs are not piggish at their finely set troughs.

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

I LOVE reading your entries (or is it entrees?). You are gifted, my friend!

Jim, the few years that I knew you as one of my Beer and Wine customers, I never realized what a verbally eloquent man you are! I enjoy your writings very much!

John

PS…. I hope you and your family have a wonderful Christmas/ Holiday Season

Thanks, John. I hope the holidays bring you peace, health and joy.

Hi Jim,

So delighted your back at it.

I need these giggles to start my day, a smile on ones face is always better than a frown

because your body hurts more

as you age. We’re both lucky to be here. Never stop dancing.