To some, fifty-four years might seem a long time to hold a grudge. Of course, if your last name happens to be Hatfield or McCoy, fifty-four years is nothing. Hell, it barely spans four generations of those gawd-fearin’, snake-handlin’ ridge-runners.

My grudge is about an egregious moment in time when my parents wronged me by not allowing me to take a class in automotive mechanics. This single event has led me to spend countless thousands of dollars in car repairs that could have been avoided if, for example, I had ever been taught whatever it is that an alternator does.

And, as long we’re on the subject, where exactly does engine oil go after we’ve filled the reservoir?

A week or two before my first day of public high school my parents and I went to see what was then called a Guidance Counselor. I don’t remember his name, but I do remember that his face was rather interesting in that it appeared to be one-dimensional—like a child’s drawing, perhaps. After cursory introductions and a welcome that seemed foreboding, we got down to the serious business of planning my academic future. Why I’m including myself in that gathering is something of a mystery. I was never asked about any of my preferences as my mother, mostly, did the talking, along with Mr. Flatface. My father sat quietly and nodded, knowing full well that there would be serious consequences if he didn’t.

It was agreed that I would be on a college track which made certain assumptions about those courses I would be required to take. English composition, literature, four years of math, biology, chemistry, physics, social studies and history, physical education and Latin were neatly penciled in on a graph. My only elective would be band. Although I would have chosen a language that was spoken anywhere other than inside a Catholic church, my mother argued that Latin would improve my English studies which, actually, I didn’t know needed improvement. Since English is a Germanic language, her argument made no sense.

Be all that as it may, I finally was allowed to speak after clearing my throat a few times. I spoke of a mild interest in auto mechanics and asked if I could take such a course. From their reaction, I thought I had attained a new level of comic achievement. Proceeded by three audible gasps, their laughter could barely be contained, with Mr. Flatface recovering just enough to remind me that I was on a “college track” and that auto mechanics, shop and drafting were not available to me. Nor was home economics, a class that my sister had to take in spite of her being on a college track that led to five degrees.

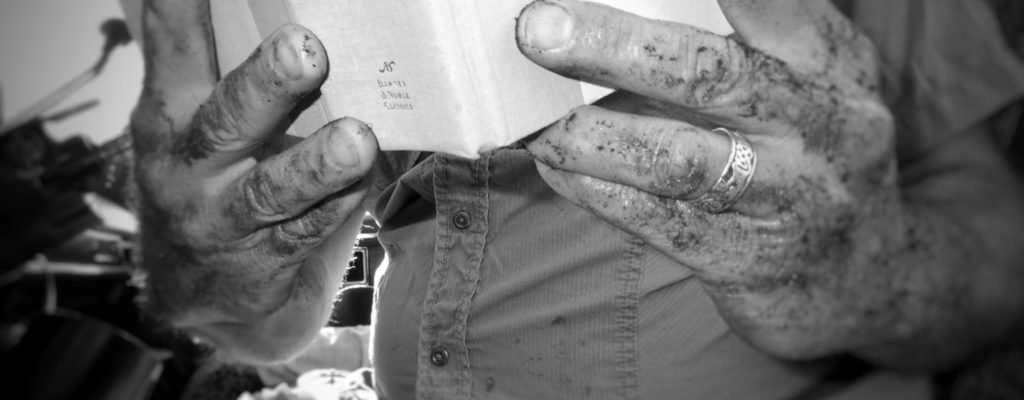

I wasn’t given to do much sulking in those days, but I let my parents know, in no uncertain terms, that I was not happy about their course selections for me. I would have been happy taking English composition, literature of both the American and European varieties, history, French, and auto mechanics. I expressed my concern that while I would be suffering through Chaucer and reading Cicero’s reflections on the Republic, my friends would have admirably dirty hands from tinkering with cars for 50 minutes every day.

I only attended public high school for two years. My last two were spent at Interlochen Arts Academy, where there was little interest in things like math and science. There I pursued literature, writing, music and broadcasting. I took a class in ecology, the highlight of which came when we drove to a nearby river to watch in horror people literally beating the water with clubs and bats to kill coho salmon that were being distressed by a lesser fish known as the alewife. Later in the term we watched the instructor dissect a swan he had found somewhere.

My early instincts about my education were correct, although I will always greatly value a liberal arts curriculum. It’s been fifty-two years since I last tried to solve an algebraic equation. The only other science class I took was biology, in which we dissected a frog or two and made a leaf collection whose only value came when I sold it to an in-coming freshman for $15 the next year. We also watched an animated film strip of a guy getting an erection which provoked the appropriate reactions. I’ll never have a conversation in Latin because I learned it as a written language, not as a spoken one. I don’t know any of the pronunciations.

I read and write every day of the week, and I listen to music with an educated ear. For five years I had a radio show in Los Angeles. I am deeply concerned about the planet’s ecology.

But I don’t know how to work on a car and I wish that I did because every car I’ve ever owned (especially the 1938 Cadillac hearse I owned for about three months) has needed lots of work that I’ve had to pay lots of money to have done.

My first car was a 1962 Chevrolet Bel Air—boxy and four-doored in a faded gunmetal gray. It was a chick magnet in the way a gourmand might be attracted to a box of Saltines. I bought it from my grandmother in Nebraska and drove it back to Chicago, leaving a cloud of carbon that might still linger over much of Iowa. At the time, I thought there was some kind of mysterious fire that didn’t produce flames.

Once, something happened to it and a friend told me I needed to rebuild the carburetor. He said it was easy. I went to an auto parts store where I had never before felt so out-of-place. I was the only guy there wearing a collared-shirt. I bought the kit and took it home, where I rebuilt the carburetor on my kitchen table over the course of five or six days. When done, I only had five little pieces of stuff left over, but I reinstalled it anyway. The car worked just fine. Until it didn’t.

Geri knows enough about cars and their inner workings that at once upon a time would not have even been considered proper. I learned this about her on our first date, when she told me about her car: “It’s a ’71 Mustang convertible with a 351 Cleveland engine—a racing Pantera—with a factory-installed Hurst tranny.”

She actually said “tranny.” I was too proud to ask what a “tranny” might be.

Despite that, I have been in charge of all of our cars’ maintenance, which is as unapt as Geri, the Irish lass, being put in charge of dinner. My idea of maintenance usually involves my opening the hood, looking down at all that metallic stuff that blocks the view to the surface below, and somberly announcing, “I think it needs to go the shop.”

My diagnoses are always met with, “Just check the fluids, dipstick.”

Many years ago we were driving a Dodge Caravan through Utah when the car stalled and died on the side of a country road. It magically started an hour later, and we drove another hour until it stalled and died again. Again, it magically started, and we drove on for another hour. This annoying pattern repeated itself until we arrived in Nephi. It was a Sunday and it was 104 degrees.

I wandered around the truck stop looking for somebody with admirably dirty hands. The guy I found responded to my tale of woe by shouting at me: “Fuel filter! Replace it!”

I could more easily perform an appendectomy, I remember thinking.

A car parts store guy with admirably dirty hands delivered a new fuel filter, but didn’t offer to spend the rest of the afternoon changing it for me. And so I began: I crawled under the car, located the old one, took it off, discovered the wonder of having a gallon or so of gasoline pour directly onto my face, and then gave my young children their first exposure to some really nasty words in a loud, clear voice.

I was afraid to light a cigarette for three days, lest the gas fumes lingering about my face ignite.

We got as far as Provo, following our new driving protocol—an hour on, an hour off.

I had a friend in Los Angeles, who I’ll call Dale, which seems only fitting since that was his name. He might have been the real-life role model for the original MacGyver, a mid-’80s television program that co-starred a roll of duct tape. Dale was as serious a car guy as one could be, even going so far as banning his family from the house each Memorial Day so he could drink Scotch and watch the Indy 500 in peace. I called him and explained our situation.

“Vapor lock,” he said with such conviction that I could picture him in his STP cap. “Got any wooden clothespins?”

“Of course,” I lied, although I could see from the telephone booth a store that would sell them.

“Clip one every four inches along the fuel line. It’ll take the heat out of the line and you won’t vapor lock.”

The next morning we made it to Layton, about an hour away. We waited the perfunctory hour and drove to a dealership.

“Fuel pump,” a young mechanic announced. As the van went up on the lift, he noticed the fifty-four clothespins grasping the fuel line. He called over the other mechanics in the shop and they all started pointing and laughing at the sight, offering no sympathy even after listening to my sad story.

I had to do something to restore whatever shred of dignity I might have had left.

I started asking them which was their favorite tale from Chaucer, and what they thought of Cicero’s politics and statesmanship. I wanted to say something in Latin, so I crowed, “Veni, vidi, vici” with all of the vocal authority of Pavarotti singing Puccini’s Nessun dorma.

The young mechanic with the admirably dirty hands whispered, “In Latin, the ‘v’ is pronounced like a ‘w’.”

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

Irish Hamburgers

Contrary to popular belief, Irish cuisine can be very exciting and satisfying, provided it’s not cooked by an actual Irish person. This has been a family favorite for what seems like forever. It might offer some comfort in these trying times.

1-1/2 # ground beef

½ c. dry bread crumbs

3 Tbs. finely chopped onions

1 tsp. Worcestershire sauce

1 egg

Salt & pepper

2 Tbs. butter

1 medium onion, chopped

2 carrots, chopped

2 stalks celery, chopped

1 Tbs. flour

1 cup cream

1 can of cream of celery soup

2 Tbs. chopped parsley

Combine the beef, bread crumbs, onion, Worcestershire and egg in a mixing bowl. Season with salt and pepper. Form into six or eight patties, or even seven if you just want to be weird.

Fry the patties in butter until well browned (but not cooked through) and remove to a baking dish.

Add chopped vegetables to pan drippings and sauté until tender. Add flour and stir until well-blended.

Combine cream and celery soup and add to the vegetables.

Pour sauce over the patties, cover with foil and bake at 350° for one hour.

If you’d prefer not to use the soup because you’re fussy, substitute with one cup of bechamel. Frankly, the soup works just fine.

Great story Jim!

Hello, Jim

Liked your Veri, Vidi,Vici blog a lot!

Reminded me of years ago when Mike and I were driving to Cleveland from Montana in an 1980s Buick Electra. At about 50 miles from Dickinson, N.D. the Buick put itself into Reverse without any help from the driver.(Mike) It would not switch gears despite a lot of tire kicking, steering wheel wrenching, hood pounding, and swearing. how we limped along crawled ( backwards) into Dickinson remains a mystery, as do the 3 days we were stuck there, waiting for the Buick to get into gear. there wasn’t much going on in Dickinson then, or if there was, we definitely missed it. And nobody we met spoke Latin.

Happy Mothers Day & Happy Spring!!

Love E.A

P.S. So Sorry about the first Entry I (Betti) didn’t see it.

Charming and Lovely~ I liked the ending!

Reminds me of Jon, so smart, reading books all the time. ❤