During my youthful stumbling around in search of a direction I might find for my life, I showed up one day at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana. I hadn’t applied or filed any paperwork, but I had rented a small, barely off-campus apartment and I just assumed that the head of the percussion department at the school of music would take me on as a student after an audition.

I played some timpani, some xylophone, and some snare drum. We talked. It’s not entirely clear if it was my audition or my chutzpah that won him over, but the next thing I was across the Quad and writing a check to the registrar’s office to re-start my college career. I was twenty-two years old. It was 1973. Tuition was $400 per semester.

A declared music major, I studied percussion with Tom Siwe, music history with Stuart Smith, and composing under Herbert Brun, the Berlin-born, Jerusalem-educated pioneer in electronic composition whose vigorous intelligence perhaps would have equally served the philosophy department. He was vastly erudite—an iconoclastic figure whose opinions ranged from the arcane to the sublime. He died at 82, in 2000.

He was not a guy you’d talk with about the weather or the Cubs.

The class of twelve student composers met bi-weekly around a large conference table. We smoked cigarettes, drank bad coffee, and talked about everything except music, as I recall. He assumed, I believe, that each of us was proficient enough in music theory to compose something. He wanted us to find Euterpe through the exploration of ideas and intellect. The diminutive Mr. Brun led each discussion, typically by introducing an idea or concept that was meant to deeply challenge our minds and beliefs. Perhaps even to offend. Frequently, the subjects were focused on religion (Jewish-born, he was a devout atheist) and freedom. He fervently believed we had too much religion and that freedom could never be fully realized until religion was entirely out of the picture.

To paraphrase his introduction on the first day of class: If you have given yourself to religion, then that was the last decision you will ever have made because every future decision will be defined in accordance with a belief system that is defined by rigidity and the absolute. There is no freedom of thought, and therefore, no possibility to create—the activity of freedom.

Well, there was something to chew on.

I think the flaw in the professor’s argument is that he believed that an assumption of faith was a complete devotion to the tenets of any given religion. It was literally absolute, with no room for interpretation. That, of course, is not the case. The simple beliefs of Christianity have given rise to various movements that exact from the texts whatever it is that pleases the believer. By most standards, the behavior of many of our elected officials in recent years is not in sync with any agreeable moral standards.

Lying, cheating, stealing—pretty much looked down upon by most of us, even the non-believers.

My composing ambitions were sidelined after the first semester. While I certainly enjoyed our composition seminars, I was less-than-impressed with what work my fellow students were offering. And the good professor was not particularly impressed by mine.

At a new music recital to which I had contributed a short piece for eight percussionists, I was rather roundly chastised for laughing—out loud—at a composition that involved four or five Slinkys cascading their ways down a hollow interior door placed at a 45-degree angle to stage floor. Music is far more serious an endeavor than I afforded it.

I got much more emotional pleasure from John Cage’s formidable 4’33”, the four-and-a-half minute-plus composition that requires a pianist to not play the piano. I’ve also harbored thoughts that the Cage piece would make for an astounding encore after, for instance, a Rachmaninoff piano concerto. It would offer comedic relief.

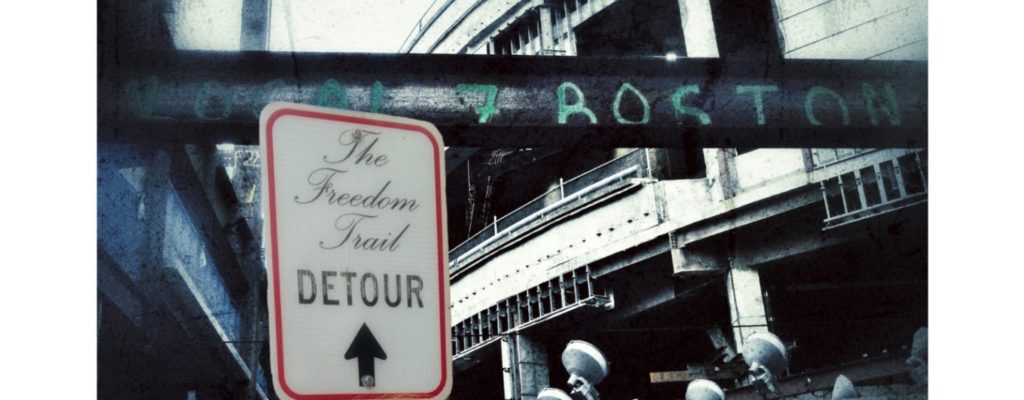

Freedom has been loudly lauded during the last eighteen months or so—mostly having to with the perceived tyranny that mask mandates impose on those who find there to be no reason to be kind or considerate to their fellow citizens.

The internet is ablaze with those unable to breathe while wearing one. Obviously, they’ve never been intubated and put on life support. (For the record, I have been.)

They are also among those who believe that Marjorie Taylor Greene possesses a superior intellect over Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), based on MTG’s theory that forest fires are deliberately set by Jewish tasers from outer space. They think T**** had the election stolen from him, that McConnell has the American people’s best interests in mind, that Gov. DeSantis is handling the COVID-19 crisis in Florida with aplomb, and that Michael Flynn, the former national security adviser, is within his rights to look for somebody in Washington, D.C. to shoot with his gifted AR-15.

Freedom, my friend Stephen, with whom I meet regularly to solve the problems of the world, is something he thinks might just be an illusion to all but the one percent. I think he might be right.

Freedom has perhaps become a commodity. If one is capable of buying justice, then one is free. My nephew is incarcerated in Colorado. His crimes against society began with a petty theft to support both a drug habit and his young family. Things got worse. He broke parole a few times and has been returned to a private, for-profit prison environment that offers no rehabilitation because recidivism is more profitable. Considering that Colorado is a three-strikes state, he is likely to spend much of the rest of his life in jail. He’s thirty-seven years old.

The concern is not for the criminal or the oppressed, it’s for the oppressor.

An incorrect assumption is to suggest a correlation between rights and freedom. Rights are afforded the citizenry through legislative action—and any of them may be rescinded at any time for any reason. Americans have certain safeguards in place, but we witnessed four years of constitutional erosion of those “rights” by a lopsided building of the Supreme Court makeup and a marked indifference to the Congress.

Freedom is the ability to be unencumbered by restriction and, at the same time, aware of the needs of others.

If one person is denied justice, then we all are. Humanity is our work, empathy our emotion.

Photography by Courtney A. Liska

Grilled Halibut

Halibut, the least fishy of the fish family, is readily adaptable to many treatments. This is how my family has enjoyed it for countless years.

Filet of halibut

1/2 C. mayonnaise

1 T. soy sauce

1 T. teriyaki sauce

1 T. Worcestershire sauce

Combine the last four ingredients and baste onto the fish. Grill until the flesh begins to flake. Serve with wild rice and buttered asparagus.

I could not agree more…

Glad you recognized how narrow was Brun’s concept of religion. I’d add that giving one’s life over to any all-encompassing worldview — religious, political, economic, social — can inhibit creative and compassionate thinking and living.

A fellow named Krisnamurti used to say, be wary of any and all “isms.” His warning did not, of course, prevent a philosophical/spiritual movement from coalescing around him, he was headquartered for years in Ojai near L.A., because people are always looking outside themselves for answers to their unhappiness.

Good piece, as usual. Thanks.

Great piece. Happy (almost) birthday, Jim.